By Benjamin Pontz, Editor-in-Chief

The morning of July 1, 2019, Bob Iuliano sat at his kitchen table and wrote an email to the Gettysburg College community. It was his first day as the college’s president, and, as he noted in the message, the 156th anniversary of the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg. A student of history who has often cited the college’s connection to Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Dwight Eisenhower, Iuliano said that morning, “I am … inspired by Gettysburg College’s determination to use that history as a springboard to its ambitious future, and I am ready to join in that essential work.”

In the 318 days since, Iuliano, formerly the general counsel and senior vice president at Harvard, has charged full steam ahead into that work. In an interview last week, he said the job has been so consuming that he has had nary a moment to look back. Working in the shadow of a predecessor beloved by the community she served in Janet Morgan Riggs, whose 11-year tenure began amid economic crisis and institutional distress after the abrupt departure of Katherine Haley Will, Iuliano joined a college that was on stable ground, though perhaps in need of a bolder vision for the future than had been articulated in the final years of the Riggs presidency.

Iuliano and Janet Morgan Riggs toasting with hot chocolate at a welcome event in Feb. 2019 (Photo Mary Frasier/The Gettysburgian)

Iuliano spent his first months in office on a listening tour, visiting each academic department and administrative unit individually and making himself a ubiquitous presence at student functions including a Student Senate Barbeque and a climate strike. He also began work on several institutional priorities known from the outset: filling key administrative positions on the President’s Council and developing plans to help the college navigate an impending demographic cliff that promises to cut the number of students attending colleges by ten percent over the next five years, particularly in the Northeast region, from which Gettysburg has historically drawn a plurality of its students.

A first year in office marked by listening, hiring, and planning has since been upended by a global pandemic that has all but consumed Iuliano’s spring semester, leading him first to extend spring break, then to move classes online and shut down campus, and now to deal with a $7 million hole in the college budget while planning for a fall semester whose feasibility is shaped mostly by forces beyond the college’s immediate control.

“There has been no existential threat to the college comparable to what we’re dealing with now–not the Battle of Gettysburg, not the Great Depression,” said Professor of History Michael Birkner, the college’s resident historian.

Thus far, there appears to be near universal confidence that the college has the right man for the job.

Professor of Economics and Chair of Public Policy Char Weise, who served on the Presidential Search Committee that brought Iuliano to Gettysburg, said that one thing he and other members of the search committee valued in Iuliano was that he is “strategic,” someone who would have a plan to lead the institution through what promised to be challenging circumstances, even if their dire nature could not have been predicted at the time Iuliano was hired.

“Just surviving will be a significant accomplishment.”

– Char Weise

Ten months into Iuliano’s presidency, Weise says that the new president has started off on the right foot, taking genuine interest in the rhythms of campus and working to build trust before shaking anything up too dramatically.

“So far, he’s doing all the right things as far as I can tell,” said Weise.

Associate Professor of Education and Africana Studies Hakim Williams added that Iuliano appears to have a genuine desire to learn before he acts.

“He listens carefully, and he asks very good questions,” said Williams. “And the questions he asks aren’t questions that make you feel defensive. They are questions that I found to be genuine, from a posture of, ‘I really want to know more about this space.'”

In conversations across the campus community, Iuliano has received high marks for his openness and transparency even if no one can quite articulate what his agenda might entail other than weathering a storm that have led some to predict that as many as 200 of the nation’s thousand liberal arts colleges — 20 percent — will close in the next year.

“Just surviving will be a significant accomplishment,” said Weise.

This portrait of Iuliano’s first year is based on three hours of interviews with the president conducted over the past 14 months, 21 interviews with students, faculty, administrators, and employees from across the college, some of whom were granted anonymity to speak freely, and a detailed content analysis of Iuliano’s written messages to campus, speeches at public events, and article in a higher education trade publication, more than 40 pages and 20,000 words in all.

Outlining His View of the College’s Role in the World

Bob Iuliano began his tenure in a posture of listening and learning, but he also gave the campus community its first look at how he views the state of higher education and Gettysburg’s place in it.

And from the beginning, he showed a capacity to break with tradition, moving the Convocation ceremony to the opposite side of Penn Hall and shortening the proceedings due to heat. Still, he took time to advise the first-year class to engage with the college faculty, embrace difference, and take intellectual risks, themes to which he would return throughout his first year.

“Higher education is about the search for knowledge and truth,” he said in his Convocation address. “This is an aspirational goal. Today’s truth may emerge as tomorrow’s folly when exposed to perspectives once regarded as unthinkable.”

At his September installation ceremony — a term he preferred to “inauguration” for fear of the proceedings appearing too regal, two sources said (students were even less formal, calling it “Bob Day”) — he made his first public references to themes of civility, our political climate of polarization, and the college’s responsibilities in a democracy, ideas to which he would return dozens of times in subsequent messages to the campus community.

“I have great hope that we have within us the ability to surmount the polarization, the partisanship, and the parochialism that makes this no ordinary time,” he said in his address.

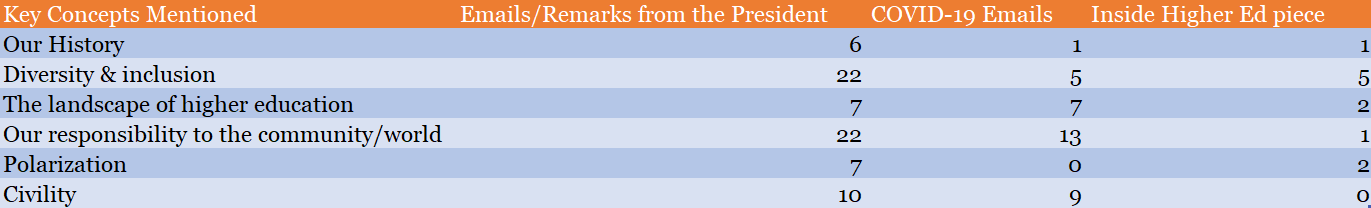

Themes mentioned in Iuliano’s speeches, messages to campus, and public writings (Content analysis Anna Cincotta/The Gettysburgian)

“As I stand here, on this hallowed ground, I do so not only with hope but with a conviction that the work of this institution is as essential as it has ever been,” he added. “This place has seen too graphically the consequences of drift, of indifference, of hyper partisanship. Society needs our thinking, our voices, our graduates; it needs people committed to the public good.”

By November, Iuliano was willing to speak in more specifics about how he saw the challenges that lay ahead at Gettysburg College. At a faculty meeting, he outlined seven areas of focus that would precede a strategic planning process he expected to begin in the fall of 2020.

- Continue to get to know the Gettysburg community

- Lead three high-profile searches to their successful completion

- Develop strategies to compete in an evolving higher education landscape

- Develop new revenue streams

- Improve retention and graduation rates

- Improve the intercultural competency of Gettysburg students

- Facilitate civil dialogue ahead of the 2020 election

While it is too early to assess all of those benchmarks, in an interview, Iuliano pointed to the work of a task force charged with articulating Gettysburg’s distinctiveness as an institution, his efforts to reshape President’s Council, and progress the college has made on belonging and inclusion as the most important areas of progress thus far in his presidency.

“I started the year with a very clear objective. I wanted to get to know the place,” Iuliano said. “I will state explicitly — and it is different here than any place I’ve been to — [a] defining characteristic is the sense of community. We say it casually and it’s easy to believe that everyone says it because they probably do, but it is actually true here. People connect to one another in a different way.”

He has referred to that sense of community more than a dozen times in messages to campus.

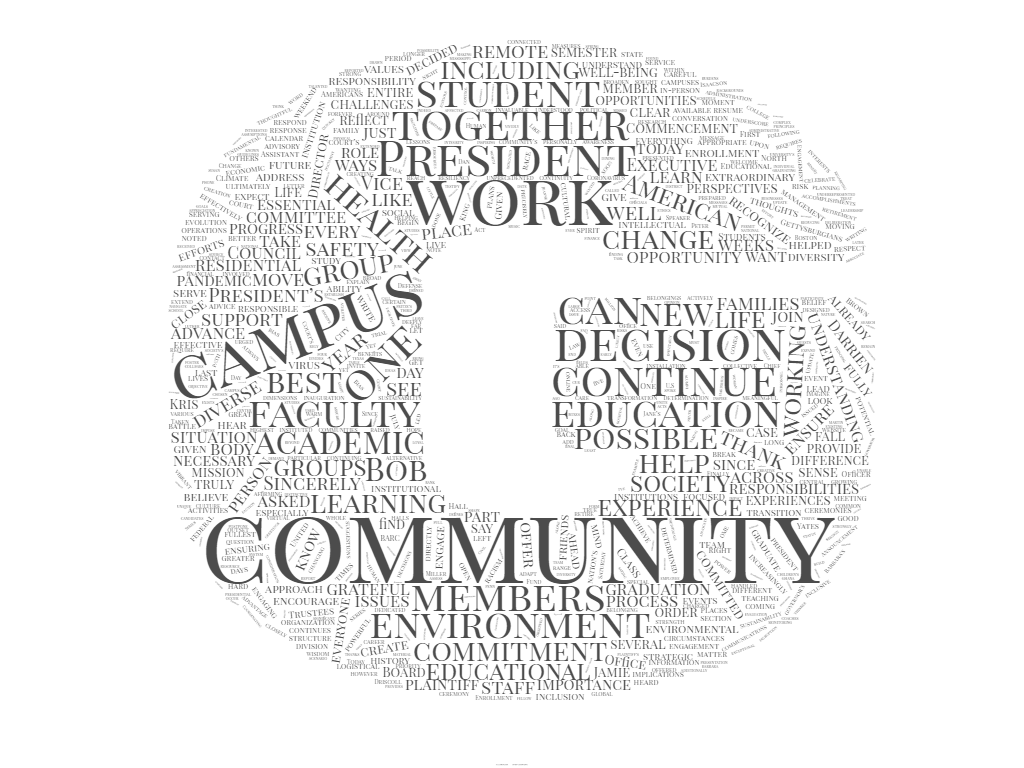

A word cloud based on more than 20,000 words of Iuliano’s writings, addresses, and messages to campus (Content analysis Nicole DeJacimo/The Gettysburgian)

As Iuliano has gotten to know the college and engaged in the work of his task force on distinctiveness, which, he says, is an effort to help an institution that has been “remarkably modest talking about itself” represent its story in a more dynamic way, he has returned to the idea that Gettysburg students are “practical idealists.”

Asked whether he views himself in the same way, he hesitated before pondering his background working as a federal prosecutor and general counsel for a higher education institution rather than pursue a lucrative legal career in private practice and then conceding, “I think that’s probably fair … I would not have applied the term to myself, but it may not be unfair.”

“As I stand here, on this hallowed ground, I do so not only with hope but with a conviction that the work of this institution is as essential as it has ever been.”

– Bob Iuliano

Defining Moments of a Young Presidency

Gettysburg’s practical idealist confronted a set of unforeseen circumstances even before students arrived on campus. Faced with tuition revenue that fell more than 10 percent short of projections from the incoming class, Iuliano directed departments to trim budgets in an effort to fill a that reached well into six figures.

Then, personnel decisions began to amass. Executive Director of the Office of Multicultural Engagement Darrien Davenport took a position at Penn State Harrisburg, Vice President of Enrollment and Educational Services Barbara Fritze announced her plans to retire, and the searches to find a permanent head of the Development, Alumni, and Parent Relations (DAPR) division as well as an Executive Director of the Eisenhower Institute needed to get underway.

People Are Policy

While Davenport returned less than two months later in an expanded position as Assistant Vice President of College Life, Iuliano still found himself at the helm of three high-profile searches. And though the three positions might have been opportunities to diversify the highest ranks of the college administration, which, at the time of Iuliano’s hiring, had only one person of color, Chief Diversity Officer Jeanne Arnold, those aspirations remain yet unmet. Only one of the three searches has led to a hire, Tres Mullis as the new Vice President of DAPR, and while Fritze has agreed to stay on for another year leading the college’s enrollment efforts, the Eisenhower Institute search has stalled without a new hire, a source briefed on the situation said.

“I think that Bob is very disappointed that these executive-level searches have not yielded diverse hires,” said Associate Provost for Faculty Development Jennifer Bloomquist, who served as the inclusion partner for the Eisenhower Institute Executive Director search and has advised Iuliano on recruiting and retaining candidates from diverse backgrounds. “I think he came in with a diversity agenda that he wasn’t entirely sure how to implement, but so far most of the executive searches haven’t yielded pools that are particularly diverse, so I think that part of his first year has been a reset — not necessarily a lowering, but a reset — of expectations, an understanding that things aren’t going to happen as quickly as he had hoped or as easily.”

Iuliano shuffled President’s Council to add Kristin Stuempfle (top left), Darrien Davenport (top right), and Jamie Yates (bottom left), while adding new responsibilities to the portfolio of Dan Konstalid (bottom right) (Photos courtesy of Gettysburg College)

For his part, Iuliano pointed to personnel moves he made in response to another vacancy on the President’s Council, the retirement of Executive Vice President Jane North, as evidence that the diversity of the senior level administration is improving.

Davenport was promoted to oversee human resources, liaise with the Board of Trustees, and serve on President’s Council while continuing his post as Assistant Vice President of College Life, where he is viewed as a potential successor to Dean of Students Julie Ramsey, who has held that post for nearly three decades.

In addition, Kristin Stuempfle, who previously served as Associate Provost for Academic Assessment and is a member of the Health Sciences faculty, was promoted to Chief of Staff and Strategic Advisor, a role in which she will oversee the college’s next round of strategic planning, which will begin this coming academic year.

The two appointments bring several new elements of diversity — in addition to a set of fresh ideas — to President’s Council, Bloomquist said.

“I would like to see fewer strings often attached when we promote a black person,” Bloomquist said, referring to the multitude of hats Davenport will now wear, “but I think Darrien will be a terrific bridge between the college and the Board. Darrien has a great personality, and he makes people feel included and comfortable. I think he’s going to be great at this.”

Bloomquist said that she thinks Stuempfle will help bring an exacting set of standards and data to strategic decision making.

“Kris pays excruciating attention to detail, and she is good at recognizing risk,” said Bloomquist, noting what she thought were positive attributes for someone assuming this type of role. “When it comes to academic stuff, I think she’ll be much more likely to collaborate with faculty, and she will help take some of the pressure off of the Provost, who won’t have to be the sole voice of the faculty on President’s Council. And she comes from the lab sciences, and I think, in the past, that faculty in the lab sciences might not have not felt as supported at the administrative level as they could.”

Vice Provost Jack Ryan, who has worked with Stuempfle in the Provost’s Office for years, agreed.

“Kris is an ideal person to be in that strategic thinking position she has assumed,” he said. “She is going to be entrusted with all sorts of issues that [Iuliano] would like to pursue in the future.”

Under the Iuliano presidency, the size of the President’s Council has increased to 11 with the addition of Executive Director of Communications and Marketing Jamie Yates; of the 11, Iuliano has hired or promoted four, and more turnover could be coming over the next few years with no certainty as to how much longer Ramsey intends to stay as Dean of Students or whether Provost Chris Zappe will hold that position in the long term.

Promoting Diversity and Inclusion

Iuliano’s efforts towards diversity and inclusion have transcended personnel.

He planned to begin his new presidential speaker series with Harvard Law School Professor Randall Kennedy for a speech titled “The Infamous N-Word in American Culture” that would have headlined the annual Stop Bias at the Burg Week. (The event was eventually canceled when campus closed.)

He sent a campus-wide email condemning the reported use of racial slurs by students towards fellow students and college alumni, the first campus-wide message condemning a specific bias incident in recent years. That did not go unnoticed by both students and faculty to whom we spoke.

And even before that incident, he convened a group of students to advise him on issues of diversity and inclusion. That group was working to include bias education as part of the first-year orientation experience when campus closed, Iuliano said.

Holly O’Malley ’20, a Spanish and mathematical economics double major, was part of that student group, which, she said, had several meetings including at least one at the president’s house. She said that Iuliano’s communications to campus affirm that supporting inclusion and belonging on campus lies at the heart of how he approaches his presidency.

“He always tries to tie things back or make sure that he is cognizant of the importance of having diverse opinions and diverse backgrounds,” she said. “In doing that, [he focuses on] making sure that our community is including those ideas in conversations in how we teach in the classroom, learn in the classroom, and what we’re doing outside of the classroom.”

The president is not new to these conversations. When he was general counsel at Harvard, Iuliano led the university’s fight against a lawsuit that challenged the institution’s consideration of race in the admissions process. In October, the U.S. District Court of Massachusetts sided with Harvard University in that case. Iuliano, hailed the decision in both an email to campus and an article in Inside Higher Ed.

“I am grateful for the Court’s decision and for its understanding that every student, from every background, benefits from the vibrant educational environment a diverse student body engenders,” he said in his campus message. “And I am grateful to be part of an academic community that recognizes that diversity is a source of our strength.”

To theatre arts and cinema and media studies double major Tyra Riedemonn ’20, a first-generation student of color who served on the search advisory committee for the Vice President of Enrollment and Educational Services search, Iuliano’s commitment to diversity and inclusion is an improvement over the Riggs presidency because it has manifested itself in action, like starting a student task force.

“What I can say is him even having an idea to start something like that, and to hear it from students directly and have them be on the forefront of that and on the ground voicing their opinions, sharing what they’re seeing, from their own personal experiences or from their friends who may be experiencing some sort of bias on campus — that is an extreme jump from what I saw in JMR’s presidency,” she said.

Developing a Vision for Curricular and Co-Curricular Activities

Programmatically, Iuliano has sought to tie issues of diversity — particularly diversity of perspective — to the orientation of civic engagement he hopes the college inculcates.

Iuliano introduces the speaker at his civil discourse series (Photo courtesy of the Eisenhower Institute)

“It is an orientation that has no disciplinary limits. What I mean by that this is not just those people who want to go into government service. This is an approach towards life,” he said.

To help recruit students interested in such a focus, he launched the Eisenhower Scholarship, which aims to recruit high-achieving students with a demonstrated history of civic engagement, and he has devoted much of his early attention to the Eisenhower Institute, developing a lecture series on civil discourse and making the first visit of his inaugural welcome tour to Washington D.C. for a panel discussion on the same subject all while he co-chaired the search for the institute’s next executive director, a staff-level hire that would typically fall within the purview of the divisional vice president.

As the college heads towards a new strategic plan that will form the basis of an upcoming fundraising campaign, Iuliano said the fundamental question is how to imbue a liberal arts education with the type of civic understanding and literacy necessary to make an impact in a changing world. Co-curricular experiences, experiential learning, and the nature of the curriculum itself play into that process, he said, and he pointed to the approval of a business major and data science minor this fall as steps towards keeping the curriculum responsive to the demands of students.

Iuliano outlines his vision for the liberal arts at his Installation Ceremony on Sep. 28, 2019 (Photo Allyson Frantz/The Gettysburgian)

Moving forward, a faculty committee will begin a wholesale review of the existing Gettysburg Curriculum, which was adopted more than 15 years ago, to assess possible changes, a process the president’s office supports.

In addition to the nuts and bolts of the curriculum, that process could lead to the integration of co-curricular activities in the curriculum, a reanimation in the college’s commitment to the humanities, and reconsideration of the college’s approach to online learning, three subjects in which the president is interested, according to Ryan, who also serves as Dean of Arts and Humanities and has been at the forefront of prior efforts to develop summer online courses.

“How do you improve the campus intellectual atmosphere? You have to provide students with other opportunities. I think if you have a new curriculum that explicitly includes co-curricular activities, that might really improve the caliber of students coming to Gettysburg College,” said Ryan. “[This curricular review] is really the place that everything could emerge from. It could be the focal point of all sorts of initiatives in the future.”

The announcement of that curricular review came in December, and then students and faculty left for winter break. By the time they came back, a mysterious virus had been identified in China. That virus would come to define Iuliano’s second semester in office.

And Then, a Pandemic Happened

The college’s earliest engagement with the coronavirus pandemic came in mid-January when students who had planned to study abroad in Shanghai were advised to make other plans. As February progressed, most conversations on campus about the virus centered around whether planned college-sponsored spring break travel to places like Jordan, Montenegro, and France could proceed. In late February, shortly before spring break, the college pulled the plug on international spring break travel, but domestic trips went on as planned. By the time students scattered on Friday, Mar. 6, the college gave no indication that it anticipated anything other than a normal return a week later. That afternoon, the president invited campus to the maiden event of the Presidential Speaker Series. Some students have not returned to campus since.

By early the next week, circumstances had changed. Iuliano convened a sub-group of the Campus Emergency Response Team that began to hash out options, and, on Tuesday, Mar. 10, Iuliano extended spring break by a week. This was a less dramatic step than other colleges, such as Bucknell, took at the time, but it kept with Iuliano’s commitment to move incrementally as the situation matured and information evolved. At the time, it was not a foregone conclusion that students would not return to campus; through the week, sources say that Iuliano worked with senior administrators on a number of possibilities, but, by the end of the week, it was apparent that campus could not reopen at the end of the extended spring break.

On Monday, Mar. 16, Iuliano announced that the college would close its doors for the remainder of the semester.

“We considered, as some have urged, making a series of interim decisions. Given the view of public health experts that the virus will continue to expand domestically for the foreseeable future, and the need for families, students, faculty, and the College itself to make plans, we decided it was not constructive or appropriate to create such uncertainty,” Iuliano said in a message to campus.

He announced almost immediately, too, that the college would refund students’ room and board fees for the second half of the semester, but he held firm against any tuition refunds. The room and board remittances alone set the college back more than $7 million, exacerbating an already complicated financial picture.

“It would be easy to say that the federal government has twice rescued Gettysburg College at a time of intense difficulty in terms of its financial status.”

– Michael Birkner

Nevertheless, the college committed to pay employees through the end of April as it waited for news about possible relief from the federal government. In the end, the college would receive $1.66 million, a far cry from the lifelines the government provided during previous national crises that adversely affected higher education, Birkner, the college historian, said.

During both World War I and World War II, the college lost a significant portion of its male student population (which, at the time was a significant majority) to military service, crushing the college’s revenues. Both times, the federal government used Gettysburg and other colleges to train military officers (during World War I) and pilots (during World War II), offsetting the fiscal woes.

“It would be easy to say that the federal government has twice rescued Gettysburg College at a time of intense difficulty in terms of its financial status,” said Birkner. “There’s certainly precedent for the federal government to support these kinds of institutions, public and private, not just private, not just public, but both in times of special national emergency.”

No such aid appears forthcoming at this point, though, and, after waiting until just days before the end of April, Iuliano announced a cache of administrator furloughs, staff hour reductions, and salary cuts for senior administrators to help balance the budget for this fiscal year.

The question of what to do moving forward is growing ever more acute, and, as Iuliano plans for the fall, one of the working groups he has convened is focused on business and infrastructure continuity and includes a veritable brain trust of financially-minded college officials including Vice President of Finance and Administration Dan Konstalid, Executive Director of Financial Aid Christina Gormley, Senior Director of Budget Planning Matthew Price, Associate Vice President of Finance Chris Delaney, and Faculty Finance Committee Chair and Associate Professor of Mathematics Beth Campbell-Hetrick.

Of course, balancing the short-term financial and logistical exigencies with the long-term strategic objectives to strengthen the position of Gettysburg College lays at the heart of Iuliano’s challenge, but those who have worked closely with him think he is well equipped to balance the two and chart a compelling course forward.

“I think he’s going to do a very good job for us because he’s going to balance the pressing concerns of the moment with long-term considerations,” said Johnson Distinguished Teaching Professor in the Humanities and Professor of History Bill Bowman, who sits on Faculty Council and thus meets with the president often. “The president has enough ambition for himself and for this institution to know that we don’t just want to just stay where we are. We want to move forward.”

“The President has enough ambition for himself and for this institution to know that we don’t just want to just stay where we are. We want to move forward.”

– Bill Bowman

Iuliano said at the final faculty meeting of the year that the college must “be smarter, more creative, and more ambitious than our peers.”

In an interview, he elaborated on balancing short- and long-term considerations, noting, “I think that all roads lead, in a sense, to the same destination. And that is we have certain inherent strengths as an organization. And I think part of our work is to amplify those strengths.”

“And if it mattered before the pandemic, it matters even more so now and not just economically.”

– Bob Iuliano

“And if it mattered before the pandemic, it matters even more so now and not just economically,” he added. “As you look at the world and the way in which we’re approaching these questions — the deep societal, cultural, economic, political issues that the pandemic has raised — I want our graduates … to have a voice in the answers to these questions. I think we have a distinctive perch to be able to make that case. If I felt this work was important when I walked into Penn Hall on July 1, I can tell you as we walk into the last week of the academic semester, I think it’s even more important today.”

So, What Have We Learned?

Gettysburgians have opinions on everything, questions both big and small, and, almost always, their perspectives vary widely. What is the best kind of Servo cookie? How should the college approach integrating diverse perspectives into the curriculum? Should that gazebo hold its place in the center of campus or would it be better if someone accidentally ran into it with a bulldozer? Any of those questions is liable to garner a panoply of different answers depending who you ask.

Gettysburg’s seeming predisposition towards disagreement and even contrarianism makes it all the more remarkable that, in nearly two dozen interviews for this story with low-level support staff, senior administrators, tenured professors, student leaders, junior faculty, and campus observers, not a single person said that Gettysburg does not have the right man for the job. Even more surprisingly, more than three-quarters of interviewees did not identify a single substantive concern they had with Iuliano’s approach to the job of college president or his performance thus far.

Now surely that unanimity might be colored by the fact that the college find itself in the middle of a global pandemic and a crisis for higher education institutions such that people feel more inclined toward unity than criticism, but while some interviewees expressed doubt or uncertainty about the turbulent and lean years facing higher education, none expressed misgivings about the man who will lead Gettysburg through them even if they are not sure what the institution may look like on the other side or how it will get there.

“I don’t know yet if he has the inclination or the will or the social capital to make truly transformational decisions about the future of the institution. That’s not really a criticism. It’s just a timing issue. It’s been here less than a year, and the past few months have been completely derailed by a global pandemic,” said Janelle Wertzberger, Assistant Dean of the Library. “But we’ll see if he’s the kind of person who will take the measure of evidence and say, ‘Okay, we’re going here and here’s why. Come on with me.'”

But whenever those moments come, there seems to be little doubt what Iuliano’s animating principles will be.

“He is clearly very, very passionate about the liberal arts education, and his focus is on the students, as it should be,” said Associate Professor of Environmental Studies Andy Wilson. “I have absolute confidence that the president is the right person to bring us through this, and I think he’s going to make Gettysburg continue to thrive.”

“I have absolute confidence that the president is the right person to bring us through this, and I think he’s going to make Gettysburg continue to thrive.”

– Andy Wilson

Members of the faculty, ever zealous guardians of their role in shared governance of the institution, have praised Iuliano’s communication particularly through the coronavirus crisis.

“He’s done a really good job communicating,” said Graeff Professor of English Literature Suzanne Flynn. “And, on the list of important leadership categories, that’s up there in the top three: the ability to communicate clearly without bullshitting people, trying to paint a rosy scenario. But also without panicking, just having the ability to calmly communicate the situation in a way that makes everyone feel invested … I think that’s his greatest strength in all this.”

Students, meanwhile, expressed appreciation that, like his predecessor, Iuliano shows up to campus events.

“Whether it be going to sporting games on the weekends or to research presentations at the end of the semester, it’s pretty neat to have your college president walking around all the time,” said Student Senate President Patrick McKenna ’20.

Lizzie Hobbs ’21 recalled that, back during Iuliano’s installation weekend, she was displaying research on World War I with the Jack Peirs project as part of a student showcase, and the president came by to chat with students even though he was already familiar with their work.

“He still took time towards the end of the event to come over and just talk to us. And he was like, ‘Hey, have you guys eaten? Because you need to make sure that you’ve eaten,'” said Hobbs. “I think it just shows that he does have a genuine amount of concern and care for people.”

It remains to be seen, of course, whether Iuliano can translate the goodwill he has built within the campus community into a successful presidency, but, in the shadows of a dyed-in-the-wool Gettysburgian who rose to the office of the president through the student body, then the faculty, and then the administration, Iuliano, an outsider, has planted a flag as someone that is here to stay. People close to Iuliano say that, privately, he has mentioned that he would like to remain in Gettysburg through 2032 to celebrate the college’s 200th anniversary.

If that happens, it will mean that the 58-year old has navigated a small liberal arts college in rural Pennsylvania through another pivotal moment in American history, weathering a pandemic, a demographic cliff, and a cultural climate that increasingly questions the value of a liberal arts education.

During an interview the morning of Iuliano’s inauguration back in September, Charlie Glassick, 88, who served as Gettysburg’s president from 1977 through 1989 said that leading a college requires bringing a lot of people with you. In that context, Glassick said, “The word ‘incrementalism’ is an important word.”

Although he has characterized his approach to the coronavirus and its fallout as one of incrementalism, Iuliano said that he is not sure that word will come to define his presidency.

“I think you make judgments about what’s necessary and appropriate for an institution in a given moment in time,” he said. “As we look ahead at multiple levels of issues, I’m not sure the best response will always be incremental. It is my instinct, and I think it has been my instinct since I’ve been president, to engage the community in the facts that matter because I do think we all should have a common baseline of information. We all should see the goal we’re heading towards. That’s not the same as incrementalism. It’s an important point about our sense of sharedness, but it is not necessarily the case that every decision has to be stepwise. Some may need to be more transformative than that.”

In the eyes of Luke Frigon ’18, once the student body president and now an admissions counselor, Iuliano has what it takes to be Gettysburg College’s president.

“I think that even though he’s someone who doesn’t fully know Gettysburg in the sense that someone who’s been here for years and years does, there is that kind of outsider bit,” said Frigon, “but every time that I’ve spoken with him or that I’ve interacted with him, he has consistently proven to me that he’s willing to do the work to become a community member, and to be an engaged community member. At the end of the day, that’s what we do.”

Anna Cincotta, Nicole DeJacimo, Phoebe Doscher, Mary Frasier, Lauren Hand, Gauri Mangala, and Maddie Neiman contributed to this report.

Editor’s Note: The author of this article served as a student representative on the search advisory committee for the new Executive Director of the Eisenhower Institute. His last engagement with that search was an on-campus meeting in February, and, since then, he has been apprised of no new information in his capacity advising the search. No information from that process has been incorporated in this article.