By Benjamin Pontz, Editor-in-Chief

Listen to this story:

At the Feb. 2, 2006 meeting of the Gettysburg College faculty, then-Provost Dan DeNicola announced that the college had a problem. The Carnegie Foundation, which classifies colleges and universities nationwide, had announced that its subsequent classifications would include subgroupings. Gettysburg’s classification could then shift from strictly a liberal arts college to an “arts, sciences, and professional” institution, which would group Gettysburg with colleges in which more than twenty percent of the population is enrolled in a major outside of the arts and sciences. The fear, DeNicola said, according to the meeting minutes, is that this could adversely affect the college’s national rankings in publications like U.S. News & World Report by grouping Gettysburg with a set of institutions that were not liberal arts colleges.

At the time, more than 20 percent of the degrees the college conferred were in Management. DeNicola identified three possible solutions: ignore the rating and continue building the Management program, find a way to limit the number of Management majors to below 20 percent, or eliminate the Management major, possibly replacing it with a minor.

Then-President Katherine Will charged a task force later that spring to study the issue and make recommendations. The task force was chaired by DeNicola’s successor, Janet Morgan Riggs, who, at the time, was a Professor of Psychology serving as Interim Provost.

That fall, Riggs came back to the faculty with a report that recommended continuing to increase the academic rigor of Management Department courses (a movement that was already in progress after a curricular revision in 2003 that came on the heels of several negative external reviews of the department) while separating the program into a major that focused on studying Management as a liberal art and an advising program that would allow students from across the college to develop business skills.

Ultimately, the Management Department accepted many of the task force’s recommendations, eventually redeveloping the department’s major as Organization and Management Studies (OMS), which the faculty approved in 2009, and developing a minor in business that was first awarded in 2010. As it turned out, U.S. News & World Report continued to use only the primary classifications in its rankings, so the college remains weighed against other liberal arts colleges even if it awards more than 20 percent of its degrees in pre-professional domains.

Glossary of Names & Titles

- Duane Bernard, Lecturer of Management

- Dr. John Cadigan, Chair of Faculty Finance Committee & Economics Department

- Dr. Brendan Cushing-Daniels, Harold G. Evans Professor of Eisenhower Leadership Studies & Associate Professor of Economics

- Dr. Amy Evrard, Chair of Anthropology & Incoming Chair of Academic Policy & Program Committee (APPC)

- Dr. Suzanne Flynn, Graeff Professor of English Literature

- Dr. Karen Frey, Associate Professor of Management

- Barbara Fritze, Vice President of Enrollment & Educational Services

- Garrett Goodwin ’21, Co-Chair of Student Senate Academic & Career Affairs Committee & Member of APPC

- Dr. Brian Meier, Chair of APPC & Professor of Psychology

- Dr. Jeff Oak, Vice Chair of Board of Trustees & Chair, Trustees’ Academic Affairs Committee

- Dr. Heather Odle-Dusseau, Chair of the Management Department

- Dr. Janet Morgan Riggs, President, Former Provost & Member of 2006 Task Force

- Dr. Jack Ryan, Vice Provost & Member of 2006 Task Force

- Dr. Patturaja Selvaraj, Assistant Professor of Management

- Dr. Charles Weise, Professor of Economics, Chair of Public Policy & Former Chair of Management

- Dr. Christopher Zappe, Provost

The Background

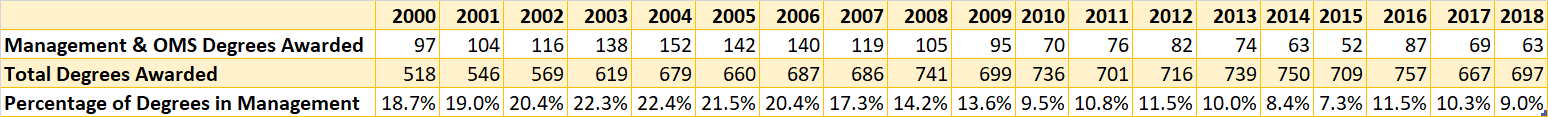

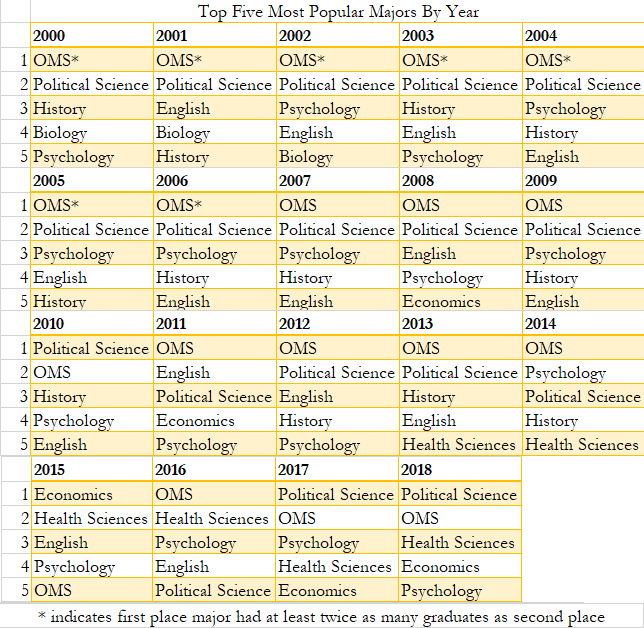

OMS has continued to be among the college’s most popular majors while Business has emerged as the college’s most popular minor. Since 2000, in only four of nineteen academic years has another major awarded more degrees than Management or OMS.

Note: Before the Class of 2012, the Management Department’s major offering was called Management, not OMS. For clarity, this data encompasses whatever the department’s major offering was at the time as “OMS”(Compiled by Benjamin Pontz/Data from Office of Institutional Analysis)

However, the number of OMS majors has steadily declined since a peak of 154 in 2004, and, in three of the past four academic years, another department has awarded the most degrees to graduating seniors.

Since 2012, two years after the business minor was introduced as an outgrowth of the pre-business advising program suggested in the 2006 task force’s report, it has been the most popular minor among graduating seniors. Many OMS majors also add the minor. In 2018, 60 percent of graduating OMS majors had minors in business, and, over the past five years, that figure has not dipped below 54 percent according to data provided by the Office of Institutional Analysis.

A Proposal to Add a Major in Business

Against that backdrop of ongoing and significant interest in studying business and related fields, the faculty has spent the latter part of the spring 2019 semester weighing a proposal from the Management Department to add a dual major in business, a new program that would be offered in that department alongside the current OMS major and the business minor.

Informal discussions that led to this proposal began as early as the spring of 2017 when Vice President of Enrollment & Educational Services Barbara Fritze and Provost Chris Zappe mentioned to several faculty members that the Admissions Office was seeing an increase in the number of students who wanted to study business and that, without having business as a major, it was becoming difficult to continue conversations with those students about choosing Gettysburg.

Fritze noted in an email to The Gettysburgian that data from the College Board show that business is the second most common intended major from students who take the SAT.

“There’s a demand for it that we should be poised to respond to,” she said.

Members of the Board of Trustees have also expressed interest in the concept of a major in Business.

In an interview, Zappe insisted that neither he, President Janet Morgan Riggs, nor the Board of Trustees have issued a directive that the faculty adopt a business major, though he acknowledged that he believes it is a matter of pressing concern.

“No orders have been given by the president or myself. We’ve been encouraging the faculty to think about this,” Zappe said.

Interactive Timeline

(Timeline designed by Gauri Mangala/The Gettysburgian)

The Timeline

In Feb. 2018, just before that month’s tri-annual Board of Trustees meeting, Zappe and Fritze invited faculty members from the Departments of Management and Economics to meet and discuss the possibility of a major in business. After that meeting, Zappe said that Management faculty expressed a desire to take the lead in developing the proposal.

Dr. Heather Odle-Dusseau, who chairs the Management Department, said that she and her departmental colleagues met several times over the course of that semester and the subsequent summer, including a day-long retreat, to consider what a business major could look like at a liberal arts college like Gettysburg.

While they considered whether the major should be available as a track within the existing OMS major, they ultimately settled on adding a new major to their department.

“We just went through an external review in the spring of 2018 … and that review was overwhelmingly positive,” Odle-Dusseau said. “And so it was really clear to us that the OMS major wasn’t something that needed to be altered in order to meet the demands of students.”

On Aug. 30, 2018, at the first faculty meeting of the year, Riggs announced that a proposal for a major in business that would be available only as a dual major and would have strong interdisciplinary connections was in development.

That November, the Management Department held an open meeting for faculty members to share their ideas about a potential business major. Odle-Dusseau reported that faculty from across campus came and that ideas for interdisciplinary courses began to emerge.

The department continued to work on the proposal over the ensuing months.

On Jan. 31, 2019, Odle-Dusseau asked Professor of Psychology Brian Meier, who chairs the Academic Policy and Program Committee, if there was a form or format for the department to submit its formal proposal. On Feb. 18, Meier provided two past proposals for new majors he had received from another member of the committee.

The Management Department submitted its proposal to APPC on Feb. 23, and, at the Feb. 26 meeting of APPC, Odle-Dusseau met with the committee to discuss the major, which APPC also discussed in private.

Meier said that the committee’s initial impressions were favorable, but that a number of concerns rose to the fore that led him to conclude the proposal “probably just wasn’t ready yet.”

Chair of Anthropology Amy Evrard, who was a member of APPC during the 2018-19 academic year and will chair the committee beginning in the fall, added, “We knew faculty would have a lot of questions.”

On Mar. 1, APPC provided its initial comments to the Management Department, which responded with a second revision on Mar. 10, the Monday of spring break.

At its Apr. 2 meeting, APPC discussed responses it had received from Zappe, Odle-Dusseau, and Lecturer of Management Bennett Bruce to written questions. According to the minutes from that meeting: “A broad range of questions regarding the nature and scale of the major, the resources required for effective staffing, and the rapid pace at which the proposal has been brought forth were discussed at length. The Committee unanimously recognized the need for a Business Major; however, the Committee was not able to support the proposal in its current form.”

Meier noted that APPC could not have sponsored the motion anyway because it had yet to be reviewed by the Faculty Finance Committee.

Odle-Dusseau expressed frustration with what she called “inconsistent” feedback from APPC, noting that it made comments on the second revision to parts of the proposal that were already in the first revision.

“It would have been helpful for them to identify the points that they wanted to make earlier on, and we could have addressed some of those instead of trying to address them after the fact,” she said. “That’s not consistency. When we try to publish papers in peer reviewed journals, the editors and the reviewers make their comments, and you submit your revision. It would be inconsistent if they went back and said, ‘Oh, you need to do this and this and this also. We’re tacking on additional things for you to do.’ That’s not a consistent way of reviewing a proposal.”

Meier said he could empathize with that frustration but that it is natural for people to have new questions the second and third time they read anything.

“It is routine to see new comments on revisions,” he said. “We do not like it as authors, but it happens. It is even more likely to happen on a committee like APPC that has 12 members from all areas of the college who all have opinions.”

Two days after APPC decided not to sponsor the motion, Odle-Dusseau and Bruce presented the proposal as a motion from only the Management Department at the full faculty meeting.

At that meeting, concerns arose about the program’s curricular focus, management and oversight, and financial viability.

Odle-Dusseau and Bruce presented a revised proposal at the following meeting, on April 18, that contained a new advisory committee that would meet occasionally to discuss the program’s interdisciplinary connections and moved the declaration timeline back from the end of the first semester of sophomore year to the end of the second semester of sophomore year.

After another entire meeting spent discussing the proposal, the faculty voted to postpone a vote to the final meeting on May 2. Before that vote could happen, however, the Management Department withdrew the motion after hearing of two proposed amendments: one that would prevent OMS majors from adding a second major in business, and another that would have created an interdisciplinary committee to oversee the curriculum and operation of the major. (The final meeting of the year is typically reserved to celebrate retirements, and, at the beginning of that meeting, Odle-Dusseau said the body’s time would be better spent celebrating retiring President Janet Morgan Riggs than debating the proposed amendments.)

“Those two specific amendments were not something that we think are helpful or objective, and frankly they are just not fair to our students,” Odle-Dusseau said. “To be in a liberal arts school and to tell a student they can’t explore a particular area of study is antithetical to what liberal arts education is.”

Regarding the interdisciplinary committee, Odle-Dusseau added, “For those of us that have degrees from business and management schools — we conduct our research in those fields, we teach those courses, we offer the business minor out of our department — it seems unethical for us to be required to hand this over to an outside body that has the power to make changes to the curriculum we’ve developed.”

The Final Proposal

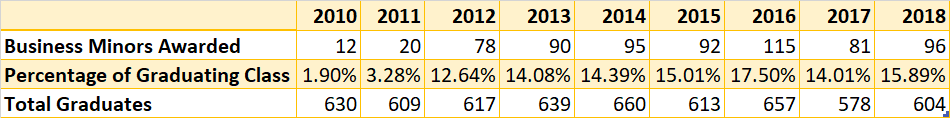

As proposed, the Business Major would require 11 courses as well as a “critical action-learning component” to apply critical theory to an experiential opportunity. Only one of those courses is required in the existing OMS major, though the statistics course could also overlap. No more than two courses from any student’s primary major would be able to count towards a major in business.

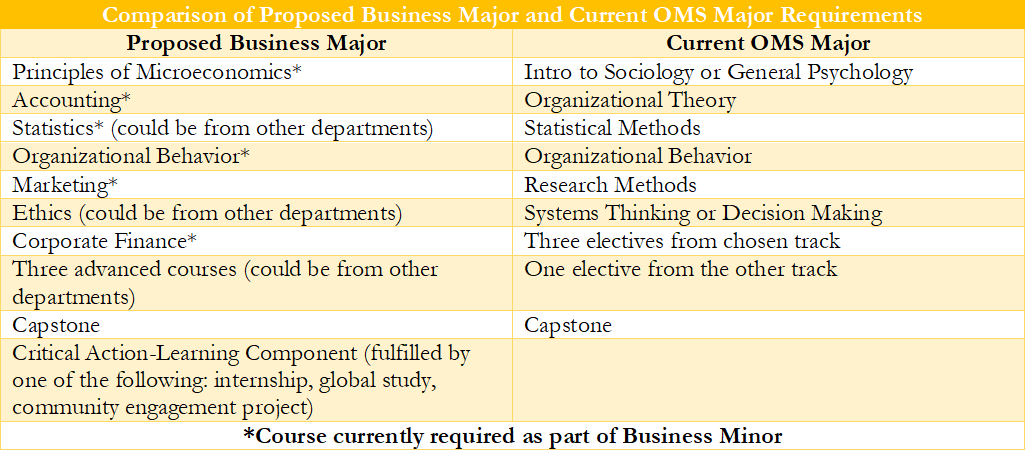

The major would be capped at 60 students per year, which is partially an effort to avoid some of the same problems from the pre-2004 Management major that, at its peak, graduated 154 students, 22.4 percent of the 2004 graduating class.

Zappe anticipates that the program would require hiring two new tenure-track faculty members, but he cautioned against thinking about that as a zero-sum game with other departments because of the potential for new fundraising.

“If there are new dollars, we don’t have to worry about whose position is not going to get filled,” he said. “I think we can start to see new dollars so that we might be able to alleviate people’s worst fears that somehow the business major would be financed off the back of declining enrollments in other areas.”

Interim Vice President of Development Betsy Diehl said in April that her division has identified more than 800 potential donors from living alumni who were Business Administration majors before that program was discontinued in 1985.

In addition to new faculty, the proposal would require a significant number of elective course offerings. The Management Department received 24 course proposals after the Provost’s Office authorized a $2,000 incentive for faculty members to develop courses that would meet the requirements of the major. Seven titles of such potential offerings were included in the formal proposal. In March, Zappe said he anticipated that fewer than 10 proposals would result in a payout.

Whether these required electives, called “advanced courses” in the proposal, would have prerequisites is unclear, but, if so, those prerequisites could add to the number of course slots completing the major requires.

The Shape of the Major

Dr. Charles Weise, Professor of Economics and the former chair of the Management Department, called the proposal that was on the table at the final faculty meeting “not as good as it could be.”

In his view, one way to approach a business major would be to focus predominantly on organizational theory, human resources, and the existing courses that are part of the business minor. In that case, he would understand housing it with in the Management Department.

However, because this proposal professes a desire to be interdisciplinary, it should require substantive contributions from other departments, Weise argued.

As possibilities, Weise suggested that the Department of Health Sciences might be able to contribute to courses on the business of healthcare, which the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services says comprises 17.9 percent of the U.S. economy, and that the Economics Department could shape a concentration in finance.

“If they want to make this a really great major, they would want to integrate finance and maybe something like business of health plus their interdisciplinary focus,” Weise said. “I think I would want [this proposal] to sort of build on strength. I don’t think this current proposal really builds on the strengths that we have at Gettysburg.”

Dr. Karen Frey, Associate Professor of Management, said that any number of narrower subfields of business could be stand-alone majors such as finance, accounting, and marketing, but that an 11-course major cannot require everything.

“[Students] are free to take courses like that as their upper-level electives,” she said. “With 11 courses for a business major, there’s not a lot that we can require.”

In terms of collaborating more closely with the Economics Department, Odle-Dusseau said she never received any indication that faculty from the department wanted to be involved in constructing the major.

The Debate

The two amendments that were in the works when the Management Department withdrew its motion reflect two of the more pronounced concerns raised publicly by members of the faculty, the first of which also cuts towards a broader question about whether this should be a required dual major at all.

Concern About Double Majors in OMS or Economics and Business

Majoring in business would require 11 courses, no more than two of which can come from a student’s primary major. Majoring in OMS requires 11 courses, of which only OMS 270: Organizational Behavior and potentially OMS 235: Statistical Methods could count towards a dual major in business. Majoring in Economics requires at least 11 courses, of which one, ECON 103: Principles of Microeconomics, would count towards a dual major in business.

Faculty members have expressed concern that allowing students to double major either in OMS and Business or Economics and Business would have students taking at least 20 of the 32 courses required to graduate from the same or a similar disciplinary perspective.

Graeff Professor of English Literature Suzanne Flynn articulated that concern at the second faculty meeting. In an interview, she noted that double majors, in general, constrict the amount of flexibility students have to explore the liberal arts. In particular, she is concerned that students double majoring in OMS and Business would take upwards of 20 courses in a single department.

While she said she has no issue with students majoring in OMS and minoring in business nor does she have an issue with other required double majors such as Public Policy and International Affairs, which she called “extremely interdisciplinary,” she has yet to see a case that the proposed dual major in business provides that same level of interdisciplinarity.

“There’s just a lot of unanswered questions,” she said, referring to what upper-level elective courses the business major would require and whether that would give the major a sufficient interdisciplinary flavor.

She suggested that one approach might be the Management Department offering a major with two tracks: OMS and Business.

“I would wholeheartedly support something like that,” she said, adding, “I appreciate how much hard work has gone into [this proposal], and I feel sorry that people are feeling attacked. Many of us are okay with a business major, just not this one.”

Flynn said she would not have the same concern about students double-majoring in Economics and Business.

Weise, however, is concerned that some students who would prefer to major only in business will choose a related field in which to double major rather than focusing on the broader thrust of a liberal arts education.

“If you double major in economics and business,” he said, “you are looking at the world from one perspective. You’re getting two-thirds of your courses from this one slice of the liberal arts, and you’re sacrificing the broader sweep of the sciences, the humanities, and so on.”

In his view, despite concerns about over-enrollment and the potential for it to become a “default major,” which he acknowledged and said would need to be addressed, business should be available as a stand-alone major.

From there, if students want to double major in Economics and Business or OMS and Business, he believes that should be permitted.

“Yes, it narrows your field of vision a little bit, but we allow for that,” he said. “If you have a real passion for those areas, that sort of compensates.”

He called the motion to ban such combinations “silly.”

Dr. Brendan Cushing-Daniels, the Harold G. Evans Professor of Eisenhower Leadership Studies and Associate Professor of Economics, said he understands the concerns that pairing OMS and Business or Economics and Business would narrow a student’s disciplinary perspective, but he said that helping students experience broad perspectives is a job for advising.

“Our — faculty, staff, students — role as proponents of the liberal arts is to help open the narrowly-focused students’ world view to the wonders of the liberal arts,” he said. “If we cannot do that, relying on artificial barriers in the curriculum to force it will produce less-satisfied graduates.”

Management faculty members took umbrage at the notion that OMS majors would not be allowed to double major in Business.

“That’s discriminating against OMS students and shows a biased view of what OMS is or isn’t,” Odle-Dusseau said, adding that she has tried to present the differences between OMS and Business but that some members of the faculty seem not to grasp the distinction.

Odle-Dusseau also compared the level of interdisciplinarity in the Business major with the Public Policy program (which Weise chairs).

“With public policy, you’ve got maybe two or three disciplines” to which one can make connections, she said, referring to philosophy, economics, and political science. “But, for us, we can make connections with people in the humanities — the languages, the English Department, with Italian Studies, and with the social sciences — we’ve got sociology and anthropology that have submitted courses. So I think that we have the opportunity to be even more interdisciplinary because of the sheer number of different disciplines that we can connect with. You literally could … have a student majoring in any other major and make connections to business, and you can’t get that with something like public policy.”

(In addition to philosophy, economics, and political sciences, courses from environmental studies, health sciences, religion, and history can count towards the requirements of the public policy major. For the public policy major’s methods requirement, courses from those departments along with biology, mathematics, OMS, psychology, and sociology are permitted.)

Odle-Dusseau added that about 50 percent of public policy majors’ first major is in political science, a related field, something she believes is fine, but speaks to a double standard to which some faculty members are holding her department.

Lecturer of Management Duane Bernard added, “It would be kind of like us saying, well, if you’re a Spanish major, you can’t major in Latin American Studies because most Latin American countries speak Spanish. I think that what [the faculty members with concerns about pairing OMS and Business] need to do is study the courses in OMS. And, if you look at them, they’re not at all business.”

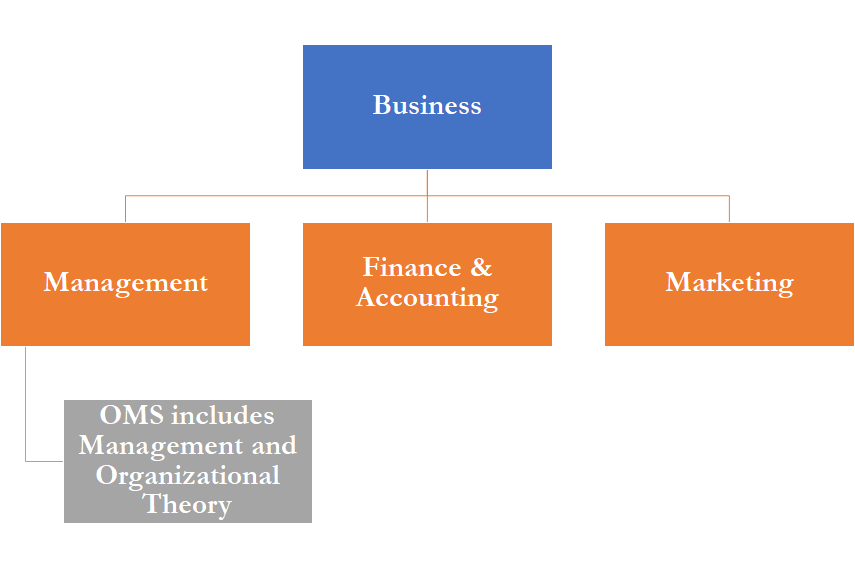

According to Management Department faculty, the field of business encompasses management, finance & accounting, and marketing, while the current OMS major focuses on management and organizational studies, an offshoot of management studies (Graphic by Benjamin Pontz/The Gettysburgian)

Forming an Interdisciplinary Committee to Oversee the Major

Current majors that require courses from across the college such as Public Policy, Globalization Studies, and International Affairs are administered by interdisciplinary committees that contain faculty members from various departments. Some faculty members, such as Weise, believe that if the proposed major is truly going to be of a substantively interdisciplinary nature, it ought to be administered by such a committee.

“We’ve got a model for how this is done, and if you want to retain the interdisciplinary nature of the major they propose, I think it makes sense to have an interdisciplinary committee behind it,” Weise said. “I understand their position that they have the expertise in business and that they want to do it themselves, but especially if they were to expand it to include finance, which they should, but now you kind of need to have economics be a bigger part of this than zero. The same if they involve other departments like Health Sciences or others.”

Odle-Dusseau emphasized that she believes it would be “unethical” for the department to have to turn the major over to a committee that could make changes to it or would be advising students.

“The business major that we propose is made up of a set of core business courses that would have to be there for us to consider it a legitimate business program, and the people in this department are best set up to ensure that this is what courses are required for students,” she said. “The majority of the courses they’re taking would be from the Management Department and the professors, and we would be the ones that are the experts in the study of business and the study of management needed to really instill that it’s legitimate.”

Odle-Dusseau disputed the notion that the major is, then, not interdisciplinary saying that, for example, just because a faculty member might have the expertise to teach an ethics course that would count towards the major, that does not mean they have “the knowledge and the education in a business or management field that would be really necessary to advise students that we’re teaching on business and management.”

Bernard added that members of the Management faculty also have professional experience in business: he worked in consulting, Bruce worked for Harley-Davidson, and Frey worked in accounting.

Garrett Goodwin ’21, a Political Science and Public Policy double major who sits on APPC and co-chairs the Student Senate Academic & Career Affairs Committee, noted that his academic advisor in public policy is a member of the Health Sciences department, which makes sense for him given that he has an interest in the pharmaceutical industry. He believes that the business major ought to operate in the same way since students could have interests in all kinds of fields relating to business that other faculty members on campus might have more expertise to advise.

Instead of a committee to oversee the major and advise students, the Management Department proposed an advisory committee that would meet once or twice a semester to “think about any potential cross-discipline connections, how we can further enhance them, or add additional ones.”

That does not satisfy Weise, who said that the committee “doesn’t really have any teeth” and may well “evolve into a nuisance for the Management Department.”

“If it isn’t really involved in the workings of the program, it’s not doing anyone any good,” Weise said, acknowledging, though, that he recognizes that the department does not want to lose control of the major. “I don’t know how that issue gets resolved.”

Cushing-Daniels said that, from his perspective, the calls to remove the major from the Management Department may be evident of prejudice against the department.

“The calls to remove the major from Management seem to me, someone with no connection to the Management department, including no close friendships … based in no small part on the low esteem in which some of my colleagues outside Management hold that department,” he said. “I think Prof. Odle-Dusseau was gracious — certainly compared to the words I would have chosen had it been me — in her gentle chastising of that ill-treatment of her colleagues [at the May 2 faculty meeting].”

For his part, Zappe said that he understands why the department would not want to lose control of the major.

“I think the Management Department worries their OMS major would be cannibalized by the business major as a second major,” he said, noting a concern that Odle-Dusseau acknowledged worries her “to an extent” before adding that her department is focused on creating opportunities for students to pursue their genuine academic interests.

Zappe added that he appreciates the willingness of Management faculty to form an advisory committee, but suggested that what was proposed may not go far enough to give faculty from across campus a genuine voice in a major that could have a substantial effect on enrollment patterns across campus.

“Life is all about compromise,” he said. “Maybe what needs to happen is that the advisory committee needs to be more substantive in terms of the oversight and the development of the major.”

The Stakes

During an interview that lasted 30 minutes, Zappe referred to “the marketplace” on no fewer than seven occasions. Over the course of the academic year, he has tried to focus the faculty’s attention on foreboding demographic challenges that lie on the college’s horizon, many of which are documented in Demographics and Demand for Higher Education, a 2018 book by Carleton College Professor Nathan Grawe that Zappe admitted at a faculty meeting last fall kept him up all night. Specifically, Grawe forecasts that the decline in birthrates around the 2008 economic recession could lead to a nationwide decline of 10 percent in the number of college students by 2029.

For Zappe, such predictions enhance the urgency to develop programs that will satisfy the marketplace’s demands, one of which is the opportunity to major in business, something Gettysburg does not currently have.

“We can say that we don’t want to have a business major, we don’t want to have this, we don’t want to have that,” Zappe said. “Okay, but when we don’t have enough students, we’ll start making budget cuts. This is one we can do in a way that is thoughtful, connected to academic departments in meaningful ways.”

“When we don’t have enough students, we’ll start making budget cuts.” – Chris Zappe

Faculty Finance Committee Chair John Cadigan, who also chairs the Economics Department, concurs with Zappe’s assessment.

He noted that he served on the college’s Long Term Financial Planning Group last year. Its top recommendation, he said, was to develop a business major.

“We believe that a new business major, grounded in the principles of a liberal arts and sciences education and offered in a way that is distinctively Gettysburg, would significantly enhance the College’s long term position,” Cadigan said.

Seven members of the Board of Trustees majored in Business Administration, more than any other major represented on the Board, when they attended Gettysburg College before that major was phased out in 1985 and replaced with Management.

Although the curriculum is the responsibility of the faculty in the college’s shared governance system, members of the Board have expressed interest in driving the proposal forward.

“I think that many of the [Board members] work and operate in a world that’s very different from ours where decisions are made quickly and implemented quickly,” Zappe said. “They have this fiduciary responsibility for the well-being of the institution. Their eagerness and anxiety is motivated by love of the institution.”

In a written statement, Jeff Oak, Vice Chair of the Board and Chair of the Academic Affairs Committee, said, “The Board understands, as do many College constituents and stakeholders, how attractive a business major could be at Gettysburg College. We are thankful for the work the Management Department put into the proposal and admire the care and dialogue that ensued over the past few weeks as the entire faculty weighed this proposal. We very much appreciate the commitment from the faculty to continue conversations about a business major in the fall.”

Zappe said he is concerned that some faculty members seem to view the potential of a business major in terms of how it would affect their departments rather than how it would create more opportunities for more students to study more perspectives.

“If we are not responsive to the marketplace, we’ll have fewer students overall, and then we’ll have majors and minors that are not sustainable,” he said. “I’m not trying to frighten people; I just think that’s what’s coming if we don’t respond to the marketplace.”

He added that some students who have been admitted to Gettysburg do not come because the college does not have a business major and many more never even apply.

Goodwin said that he would major in business if Gettysburg offered it and that he considered majoring in OMS before. During a summer internship, he says he asked a senior executive at a major corporation if that major would provide him enough skills to succeed in business and was told that it was missing courses in major competencies like accounting. So, he decided to major in public policy instead.

He said he understands the reticence to create majors focused on pre-professional preparation, but noted that, ultimately, students need jobs.

“Gettysburg can add a liberal arts flair to a pre-trade major,” Goodwin said. “Skills are what gets a person hired.”

In her final address to the faculty at its May meeting before her impending retirement, President Riggs hit on a similar theme.

“The world around us is changing so quickly, and Gettysburg College needs to continue to change with that,” she said. “That does not mean compromising on our mission, that does not mean we should be less careful in our decision making, but it means being ready to meet the needs and expectations of today’s and tomorrow’s students, and that includes both what we teach and how we teach.”

In a May 16 interview with “On Target,” The Gettysburgian‘s podcast, she elaborated.

“The goals that we have for our students in terms of personal fulfillment, civic engagement, and contributing to a democracy actually fit beautifully with those same goals that help to prepare students for the workplace,” she said. “Many times we feel like talking about professional preparation is not as lofty or not as important, and my sense is, no, we need to be talking about that too.”

She added that the proposal the Management Department put forward, in her view, fits with that mission.

The Fallout

A pervasive feeling among faculty members, both those who support the proposal and those who have reservations, is that it was rushed to the floor at the end of the semester without sufficient time for all the questions and concerns that faculty members may have to be aired.

Cushing-Daniels believes more time would have led to the amendments that were ultimately in the works being voted down and the proposal being passed.

“If this proposal had been submitted to the faculty two months earlier, we would easily have addressed enough of the concerns — and avoided the sense of being rushed — and the proposal would have passed by a wide margin,” he said.

Zappe echoed the desire for the faculty to have had more time this spring to review the proposal, but he said he did not blame the Management Department for the process it undertook.

“When you’re teaching, advising, mentoring students, doing research,” he said, “it’s hard to do all these things during the academic calendar. If we had brought proposals to the faculty in early March, we would have had time to have more conversations. I think the unfortunate thing is that some people thought there was an effort to push it through. That wasn’t the strategy at all. The thought was, let’s get people’s feedback and revise. We might be in a different place if we had started in March.”

The Management Department contends that factors outside of its control held up the proposal during the spring semester, noting specifically that it took APPC almost three weeks to give them guidance on what information needed to be part of a proposal and for going through multiple rounds of revision that brought up new issues that were part of the original proposal each time.

Meier said that, overall, he believes that both committee and full faculty review of major initiatives makes them better.

“New majors affect everybody, and the idea is that the whole body of faculty might make a better decision than five or ten people even if they are the experts,” he said. “The amendment process is what makes motions better. That’s why we have the amendment process. If we would have had more time, maybe people could have discussed some of these amendments. That would have been an interesting discussion.”

Vice Provost Jack Ryan, who sits as the Provost’s representative on APPC and who was a member of the 2006 task force that reviewed the Management Department, agreed that there were simply too many issues to work out in the short time the faculty had to do so.

“The bottomline is the proposal needs work, and it needs input outside of Glatfelter Hall,” he said.

Because the proposal was not approved before the end of the semester, it is unlikely the major would be able to start beginning in the fall of 2020 as originally planned, which sets back the timeline of recruiting students who might be interested another year.

“The admissions office engages in the recruitment of prospects beginning in their sophomore year in high school,” Fritze said in an email. “It’s a 3 year engagement. We are very interested in being able to share an approved major to increase the awareness of students considering college options.”

The Path Forward

For their part, the Management Department faculty members plan to spend time this summer considering the feedback they have received and bring forth another revision of the proposal in the fall.

As for what that proposal will contain, Odle-Dusseau said it is too early to tell.

“A lot of this is up in the air,” she said. “The main goal is to find a way to provide this for students as soon as we can.”

Revising the current OMS major, adding a second track for business, or sticking with the dual major framework could all be options.

“I don’t want to see OMS as it is go away,” Frey said.

Even once a version of the major is adopted, Assistant Professor of Management Patturaja Selvaraj emphasized that the department will continue to innovate and develop new courses to meet the interests of students.

“It’s like a business environment,” he said. “I think the company comes with a product which the customers need. Similarly, I think in business, so many things are changing, so when students have come up with demands for certain electives in the future, I think we will definitely, as a department, come up with those upper level electives to address … the demands from students. We don’t want to be rigid.”

Whether that intended fluidity would extend to allowing amendments such as moving the major to be under the auspices of an interdisciplinary committee or prohibiting dual majors in OMS and Business is something that the department has not yet determined.

“That’s something I’d have to discuss with everybody, and we’d have to come to an agreement in our department of how we would want to address something like that,” Odle-Dusseau said. “We’re really taken aback by these amendments and how they came so last minute.”

Conclusion

Some of those who oppose the current proposal acknowledge that the college ought to be responsive to a clear demand for some kind of major in business, but, given that up to 10 percent of each class could participate in this new program, they want to make sure the proposal meets the college’s long-term interests.

“This is why you sense that the faculty are very interested in this. If we wanted to tweak the English major, nobody would freak out. I’m not saying people are freaking out about the business major, but I think people are concerned about the shape of it because it could impact so many students if it’s successful,” Flynn said. “I hope it is.”

Zappe hopes the faculty can move quickly in the fall.

“I’m hoping we can bring this to a resolution,” he said, “so that we can impact the recruitment of students for the next cycle. If we have to make compromises, so be it.”

After a short pause, he added, “The clock is running.”

Note: The audio recording of this article was made before a few final edits of a non-substantive nature occurred.