By Brandon Fey, Staff Writer

In celebration of the 225th birthday of Gettysburg College founder Samuel Simon Schmucker (which occurs on Feb. 28), Gettysburg College hosted a celebratory day of programming in the Mara Auditorium of Masters Hall on Saturday, Feb. 24 from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. The event was sponsored by Gettysburg College, the Lutheran Historical Society of the Mid-Atlantic, the Gettysburg College Provost’s Office, the Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College, the Gettysburg College History Department and the Christ Lutheran Church in Gettysburg.

Coordinators were pleasantly surprised to find over 70 people in attendance, including Gettysburg College students, faculty and members of the local Lutheran community who came to celebrate and learn about Schmucker as he was instrumental in the founding of the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg, Christ Lutheran Church, the Lutheran Historical Society of the Mid-Atlantic and most notably, Gettysburg College.

Program presenters included Gettysburg College faculty members, instructors from the Lutheran Theological Seminary and other invited Lutheran scholars and Schmucker biographers.

The program began with an opening presentation by the Rev. Dr. Maria Erling, titled “Schmucker’s Long Shadow.” She began with a discussion of Schmucker’s origins. Having trained at Princeton, Schmucker was one of the best-educated Lutheran ministers in Pennsylvania in the early 19th century. She also mentioned Schmucker’s passion for the republican ideals of self-government. According to Erling, he was compelled to extend these values to the Lutheran church, which he believed would greatly benefit from what he considered to be the highest form of social organization. This included the value of freedom, which he believed ought to have been extended to the abolition of slavery.

Erling spoke about these visions in light of the complicated era in which Schmucker lived. The antebellum period was of substantial division among Lutheran synods (assemblies) across the United States. As the founder, first professor and first president of the new Lutheran Theological Seminary in Gettysburg as of 1826, Schmucker’s revolutionary concepts were controversial among other Lutheran leaders across the country. He was put at odds against the conservative practices of Missouri and laboriously sought to maintain unity with other congregations in light of an ongoing debate about confessionalism and ultra-symbolism.

This division was also present between northern and southern Lutherans over the persistence of slavery. The Lutheran church had traditionally not meddled in political discussion. It adopted a gag rule that forbade the discussion of slavery by ministers, mimicking the one instituted in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1836.

The following event was a panel of invited Lutheran scholars and ministers who spoke about different aspects of Schmucker’s professional career. Dr. Susan McArver was the first to speak. Her lecture, titled “‘Your Aged Friend’”: Samuel Schmucker, Ernest Hazelius, and the ‘Consequences of Controversy’” was about the personal relationship between Schmucker and prominent Prussian theologian Ernest Hazelius. She began with a discussion of Hazelius’ background in the Moravian Church, and how he was sent to teach at a Moravian Seminary in Nazareth PA. Hazelius became Lutheran after a disagreement with the Moravians over his marriage and was the second professor at the Gettysburg Seminary. He later went to teach at a southern seminary and maintained frequent written correspondence with Schmucker.

The two men later developed theological differences that were discussed in letters toward the end of Schmucker’s life. Schmucker’s vision of a more universal, ecumenical Lutheranism put him at odds with the conservative confessionalists and sacramentalists of the era. When asked for support on these stances, Hazelius replied to Schmucker that he aligned closer to the confessionalists, as he feared a lack of credence without the old books Schmucker had proposed to remove. While no letter of reply exists from Schmucker, McArver inferred that he was likely greatly disappointed at this.

The next panelist was Gettysburg College and Seminary graduate the Rev. Dr. Mark Oldenburg, who gave a talk titled “Some Surprising Aspects of Schmucker’s Opposition to Slavery.” Oldenburg began by emphasizing Schmucker’s opposition to slavery, and how it was often expressed through his teaching and writing. First, Oldenburg argued that Schmucker’s opposition to slavery came at a social cost he was willing to pay as his decision to openly condemn it was seen as controversial.

Schmucker believed that slavery was only to be abolished through a gradual process, in which Southern states would take it upon themselves after the persuasion and conversion of slaveholders. This is what he had observed in the North, and figured that it was the only way slavery could truly be ended.

Oldenburg then discussed how Schmucker’s political and theological values held that the inalienable liberties mentioned in the U.S. Declaration of Independence obliged a set of complementary inalienable duties that all ought to fulfill. He connected this to the biblical duties to honor marriage bonds and study scripture, neither of which could be properly upheld by the enslaved. He specifically argued that depriving slaves of education prevented them from studying scripture and refuted popular arguments that suggested biblical evidence for the justification of slavery.

Schmucker frequently quoted from St. Paul’s Areopagus sermon, affirming that slaves were human beings of the same level of creation as all other people. According to Oldenburg, Schmucker also recognized the involuntary slaveholding of his own experience through his one marriage and expressed his regret about the situation.

The final panelist was The Rev. Dr. Nelson Strobert, who gave a talk titled “Schmucker and Payne: Venerable Preceptors” about Samuel Schmucker’s relationship with his mentee, Daniel Payne, who would become a prominent Methodist Bishop and educator. Strobert began by discussing Payne’s background as the son of free African Americans who developed a passion for Lutheran faith at a young age. He started a school in 1829 for young black men in Charleston to teach them to study scripture. When his school was closed due to an 1835 South Carolina law, he discovered Schmucker’s writings on emancipation and enrolled in the Lutheran Theological Seminary of Gettysburg. Payne went on to preach at black churches in the South and maintained frequent communication with Schmucker until the latter died in 1873.

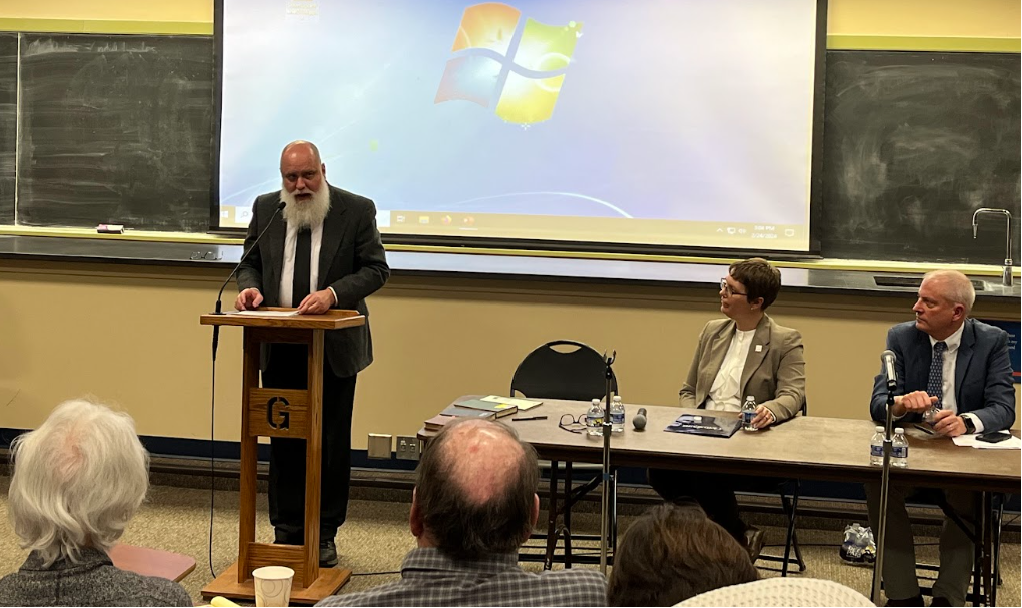

Professor Michael Birkner addresses the audience on Samuel Simon Schmucker. (Photo Brandon Fey/The Gettysburgian)

After an intermission for lunch, the programming resumed, with the much-anticipated lecture from Gettysburg College History Professor, Dr. Michael Birkner titled “Laying the Foundation of a Superior Education: Samuel Simon Schmucker’s Pragmatic Vision and the Future of Gettysburg College.” Through his presentation, Professor Birkner connected the academic values of the college’s founder to the attributes that have shaped modern liberal arts education.

Following Professor Birkner was a second panel that was moderated by the Rev. Dr. Teresa Smallwood. The first presenter was the Rev. Stephen Herr, whose presentation titled “Schmucker and the Frankean Abolitionists,” argued that while Samuel Schmucker was opposed to slavery, he may not have been active enough in that struggle to be deemed an abolitionist. Herr explained that Schmucker’s mission to unite Lutheran synods in a highly controversial time required compromise, particularly with southern Lutherans, which overshadowed his personal anti-slavery beliefs. Herr contrasted Schmucker with the Frankean Synod, which rejected compromise and outwardly preached abolitionism. The Frankeans would eventually ordain the aforementioned Daniel Payne as a minister. According to Herr, Schmucker’s preoccupation with Lutheran, and later protestant ecumenism, made the cause of slavery a lesser of his concerns, despite remaining an opponent to the practice for his entire career.

The next panelist was Associate Director of the Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College, Dr. Jill Titus. She shared a presentation called “A New American Future: Samuel Simon Schmucker and the Modern Black Freedom Struggle” that drew parallels between Schumucker’s work and the 20th-century civil rights movement. She began by mentioning a Gettysburg College student organization of the 1960s, called The Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which called for a direct action against segregation. She then discussed the beliefs of Civil Rights leader Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who, like Schmucker, had a new American vision of cooperation between people who were needlessly divided.

Dr. Titus compared Schmucker’s opposition to the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) to King’s involvement in the movement against the war in Vietnam, as both men believed the wars to have been unjust and exploitative. In addition, Titus compared Schmucker’s ecumenical vision for the unity of protestants across the country to King’s greater ideal for creating a global community of justice. While neither had been entirely successful in their visions, they both laid a foundation for later efforts of unity.

The final speaker of the program was Lutheran Bishop Matthew Riegel, who spoke about Samuel Simon Schmucker’s vision of unifying the protestant Christians of the United States, in a presentation titled “Fraternal Appel: A Reappraisal.”

Bishop Riegel began by contextualizing the state of Protestantism in America in the early 19th century. He explained that Schmucker lived during a time of schism between various denominations, fueled by debates over new liberal interpretations of theology, and political matters such as the issue of slavery. Displeased with the division, Schmucker wrote an appeal to the American churches to create a “catholic union” (unrelated to the Catholic Church) in 1838. In this, Schmucker identified several issues of division between protestant denominations and proposed a plan to unify. He cited several scriptural passages to support his vision, in addition to what Bishop Riegel considered to be an impressive amount of information from what was deemed the “primitive church,” which existed before Christianity’s first official adoption by Rome.

Bishop Riegel outlined some of the main arguments in Schmucker’s proposal, including unity in the Christian name and unity in the fundamentals of doctrine. Schmucker called for a mutual acknowledgment of sacraments and acts of discipline between denominations, and a common standard in what he considered to be “trans-fundamental creeds” such as the famous Augsburg Confession while keeping the Bible as the fundamental “textbook” for all theological discussion.

“According to Schmucker, a real Lutheran doesn’t think of himself as a Lutheran. A real Lutheran thinks of himself as a Christian,” Riegel explained.

While Schmucker’s call for unity was a revolutionary concept for the time, Riegel explained that Schmucker was okay with the existence of multiple protestant denominations, but was specifically against sectarianism, which is the belief that the structures of one’s own denomination are superior to others. This proposal was adopted by the Lutheran General Synod and garnered the interest of some outside denominations. However, despite Schmucker’s efforts, little more progress was made to overcome the intense interdenominational strife of the time.

While Schmucker did not see his vision for an ecumenical union carried out, he set a significant foundation upon which the modern World Council of Churches has based its origin. Lutherans from the General Synod now promoted greater ecumenism, and protestant sectarianism had greatly declined.

Bishop Riegel concluded the program by acknowledging the great influence Schmucker has had in the development of the Gettysburg area and as a theologian. He recalled a question that former Gettysburg College History Professor and College Historian Charles Glatfelter would pose to his history students about whether a figure is a product of his times, or made his times.

Riegel stated that Schmucker was, “A man whose times passed him by.”