Gaines Gives Lecture “Children of the Plantationocene”

By Ella Prieto, Assistant News Editor

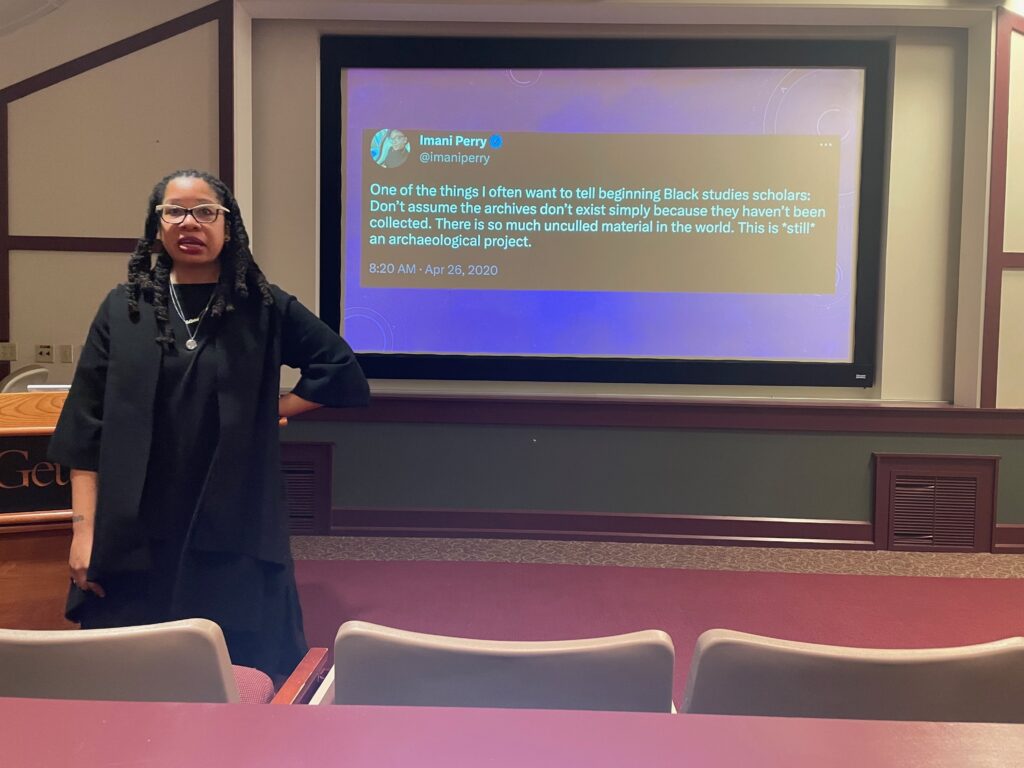

Dr. Alisha Gaines gives lecture “Children of the Plantationocene” on Thursday, April 6, 2023 (Photo Ella Prieto/The Gettysburgian)

On Thursday, Associate Professor of English at Florida State University Alisha Gaines gave a lecture titled “Children of the Plantationocene” in Joseph Theatre. The Department of Sociology Stuckenberg Fund and the Alpha Kappa Delta International Honor Society (AKD) sponsored the event.

The lecture began with an introduction by Sociology Associate Professor Cassie Hays, who described her friendship with Gaines as well as Gaine’s numerous awards and projects.

Gaines thanked Hays, Sociology Administrative Assistant Andrea Switzer, the Stuckenberg Fund and AKD for organizing and funding the event. She then began her lecture, which was separated into four parts.

One

Gaines described the way that Black Americans often have no sense of place due to their history in the United States. She told a story of her grandmother trying to describe where their family was from, which was filled with “and but maybe.”

“‘And but maybe’ is a dislocation and an unknown, shaping the contours of Black Americaness and its complicated relationship to the ideas of home,” explained Gaines.

She then listed numerous authors that have worked to identify the home of Black Americans, such as Zora Neale Hurston and Katherine McKittrick. Gaines ultimately settled on the work of “Roots: The Saga of an American Family” by Alex Haley. She explained that the nonfiction book tells the story of Haley’s true ancestor, Kunta Kinte, and those that followed him.

“Haley finding his Gambian ancestor Kunta Kinte inspired a generation to search for their own,” said Gaines.

She said that “Roots” has faced criticism, however, as many historians and scholars argue Haley fabricated parts of history for his story. While Gaines recognizes this, she added that she feels the value of “Roots” goes beyond its facts.

“This is not to dismiss the fact-checking works of historians, I promise,” said Gaines. “But to recognize how [a] story can operate in the wake of dehumanization.”

She then discussed another work of “Haley’s factional imagination,” that is titled “Queen: The Story of an American Family.” Haley wrote this work with David Stevens. This story follows Haley’s paternal grandmother, Queen Jackson Haley, who was a white-passing woman born as the daughter of her enslaver.

“Queen” focuses on the important phenomenon of “the children of the plantation,” who were mixed race and struggled to fit in with Black communities. Gaines argues that the phrase “children of the plantation” is useful in understanding how society thinks of slavery now.

She mentioned the recent increase in Black actors playing roles depicting people being forced back onto plantations: Keke Palmer in “Alice,” Janella Monae in “Antebellum” and Mallori Johnson in “Kindred.”

“It signals a sociopolitical anxiety about what could really be at stake by attempts to ‘Make America Great Again,’” explained Gaines.

She then explained Black Americans’ “complicated” relationships with plantations that are kept as historical sites. To illustrate this, she showed perspectives of plantations by multiple Black Americans, including a video of Black singer Jill Scott describing her experience at a plantation.

Gaines said most Black Americans expressed anger at these plantation sites due to their history of slavery, and the enslaved peoples who were forced to labor there, being completely glossed over. Gaines, who has visited many plantations, described her experience at them.

“Along most plantation museums, their chores still venerate Whiteness of the downplaying or the outright erasure of the Black folk who built those cherished big houses,” said Gaines. “And as they protect the furniture, writing myths about their own inheritance, who protects the memories of the people who lived in labor in the now beautiful gentrified cabins.”

Gaines elaborated that the nostalgia and misinterpretation of plantations by white Americans erases the past experience of past Black Americans, leading to Black Americans feeling the need to defend their ancestors.

Gaines shared that defending ancestors, especially in regards to plantations, is very complicated, yet she believes there is a way to do so.

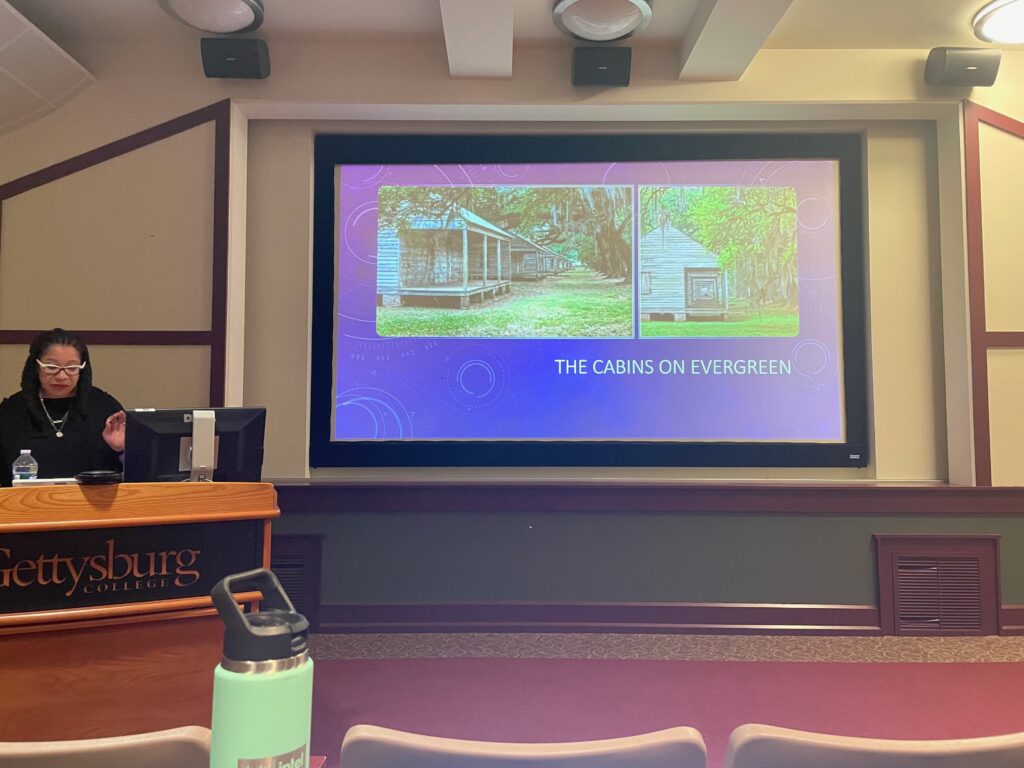

Gaines has worked with the Evergreen Plantation Archaeological Field School (EPAFS) at the Evergreen Plantation in Louisiana, which is the most intact plantation complex in the Southeast. With this group, Gaines worked to uncover parts of the plantation that slaves experienced. In doing so, Gaines believes that white Americans can reckon with their past and Black Americans can “defend the dead.”

Dr. Alisha Gaines gives lecture “Children of the Plantationocene” on Thursday, April 6, 2023 (Photo Ella Prieto/The Gettysburgian)

Two

Gaines then focused on work by Janae Davis and coauthors titled “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, … Plantationocene?: A Manifesto for Ecological Justice in an Age of Global Crises.”

“Davis et al. suggest that the spatial history of the plantation is central to understanding the nature of power in the modern world, highlighting the ways that plantation dynamics have proliferated beyond historical slave agriculture in the Americas,” said Gaines.

Gaines gave examples of this that included enclosures and reserves, industrial estates and mill villages, free trade and export zones, enterprise and empowerment zones, ghettos and gated communities and suburbanization and gentrification.

Three

Gaines then circled back to the question of how to defend the dead. She discussed the 2008 novel “A Mercy” by Toni Morrison, explaining that, “no one defends the dead better than Saint Toni Morrison.”

Gaines discussed how the novel, set in the 17th century, illustrates the modern relationship between Black Americans and plantations.

Gaines explained how the main character, Florens, is a Black slave girl sold to farmer Jacob Vaark. Florens learns many hard lessons as she grows in the novel, but her destabilizing shift is when she meets a group of white Christians that examine her and her Blackness. Florens is horrified and traumatized by this experience.

“I linger with her [Florens] here because of how she can help us imagine and reimagine the legacies of the plantation, particularly for Black America,” said Gaines.

Another aspect of Florens’s journey in the novel that Gaines focused on was her realization that all of the work slaves did on plantations had great value.

“Florens instructs us to think about the generational legacies of Black makers, recovering the plantation as a site of Black creativity, imagination, and placemaking,” said Gaines. However, she explicitly stated that this was not to say plantations were not horrible places. They were, and she noted that it is important to be conscious of that while looking at the positives of Black creations.

The other character from “A Mercy” that Gaines focused on was Lina, an Indigenous woman also bought by Jacob Vaark. Lina teaches Florens that “not everyone is equally responsible for the horribleness of this chewed world.” Thus, that guilt is not theirs to carry, which applies to the experiences of modern-day Black and Indigenous people.

Four

In the final part of her lecture, Gaines explained the end of “A Mercy,” where Florens carves her story into the wood of a room in Vaark’s house.

“While Florens never had the full vocabulary to articulate her racialized experience of captive Black girlhood, she instinctively knew her story was valuable, and worth preserving just as much as the house itself,” said Gaines. “She left an archive as if she knew this country would revere a romantic plantation past… When Florens stretches her story into the bones of the Milton Mansion, she averts every effort, both then and now, to silence it.”

Gaines concluded with the assertion that work similar to Florens’s story carved into the floorboards is incredibly important, as it tells untold stories.

“If we were to approach the plantation with an intention to hold space for the Black people that lived and labored there, we might see it as another origin story,” commented Gaines. “One of resistance, joy, love, craftsmanship. Yes, violence, terror, but also survival.”

Audience Questions

The audience then asked Gaines questions. The first question regarded the influence of capitalism on plantations and whether Gaines thought that aspect of plantations needs to be emphasized more.

Gaines answered that capitalism is not let off the hook, as the line from plantations to capitalism can be easily traced with the correct framing.

An audience member then asked about the best method to mark and recognize the sites of lynchings throughout the country. Gaines said that this can be complicated, as many lynchings occurred on private properties that cannot be marked or are unknown. She explained some of the recognition that she saw, such as plaques in Tallahassee and a lynching reenactment by a Black population in Georgia. With the latter, however, she questioned its effectiveness.

Other audience members also joined in to mention how some memorials and organizations like the Equal Justice Initiative have worked with recognition lynching sites as well.

Following this, a student asked about how the burden of proof for the belief of Black history versus European history is drastically different, with Black history requiring more evidence.

Gaines said that this unfair burden of proof still occurs today. “The very beginning of our canon starts with these threats on our [Black American’s] credibility and that persists,” explained Gaines.

Another audience member asked what Gaines thought about the smaller slave-holding sites, and if they should be recognized as much as large plantations.

“I think they’re just as important,” said Gaines. She elaborated that most slavery was farmers with two to three slaves, not the big plantations that we are prone to imagining. She added that memorializing those smaller sites is more difficult, due to them being less known.

Next, a student asked about the implications of land-back initiatives to give American land back to Indigenous people and what Gaines thought of the ecological implications of who owns the land.

“First of all, there’s no Black liberation without Indigenous sovereignty. So these things go hand-in-hand to me,” said Gaines. She explained that she supports land-back initiatives, and believes that the history of plantations also applies to Indigenous enslavement.

Another student questioned what language is used on plantation tours versus what Gaines believes should be said.

Gaines answered that what is said on plantation tours varies by plantation, and even then, it can vary by the tour guide. Gaines said tours can be harmful when guides only focus on the white family that owned the plantation and ignore the slaves that made the plantation functional. Furthermore, she talked about how plantations are currently used for weddings, parties, reunions and more. Gaines expressed her belief that plantations should not be used as venues for celebrations.

It was then asked why Gaines thought more films on Black women being forced back into slavery were premiering.

Gaines answered that she was not quite sure, but she believes it may be about “the myths of sort of the powerful Black woman and then she’s rendered completely disempowered.” She added, “But that’s also still mired in stereotype.”

The final question was about the slave reenactments that Gaines mentioned earlier, and what they entailed. Gaines answered that they can vary a lot.

She gave an example of the North Star Program at the Conner Prairie Living History Museum. This program entailed people, usually middle or high school students, pretending to be fugitive slaves for 90 minutes. She said that this was not a constructive reenactment, as nothing was learned from it.

Another example was a reenactment led by Dread Scott, where Black and Indigenous people walked the path of a slave uprising. Gaines explained that this event brought protest and catharsis, and it served the purpose of educating people about an important uprising. Because of that, it was a valuable reenactment.

Hays then thanked Gaines for her lecture and the audience applauded her work, concluding the event.