By Piper Mettenburg, Features Editor

On July 4, 2020, Scott Hancock arrived at the State of Virginia Monument in Gettysburg National Military Park equipped with a small hammer and signs reading “#FindABetterRoleModel,” and began staking homemade Black Lives Matter flags around the 41-foot monument of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. A dedicated Civil War historian, Hancock wants battlefield visitors to understand a simple truth—that the Confederate leaders memorialized on the battlefield fought to preserve the institution of slavery.

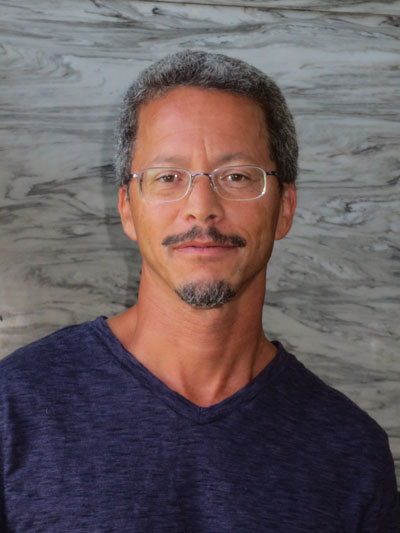

In an effort to unpack the connections between Gettysburg’s history, race, and the college, The Gettysburgian sat down for a Zoom interview with Hancock. Here’s what we learned.

Q: Do you think Gettysburg National Military Park reflects the whole story of the Civil War? Is anything missing?

The Civil War doesn’t happen without slavery, but if you go on the battlefield you would never know that. You could spend all day every day on the battlefield and that message is entirely lost. I ride my bike on the battlefield all the time, and sometimes I see school kids looking up at the Confederate state monuments. Even if they have a good battlefield tour guide who talks about the monuments, you still have these huge, beautiful bronze sculptures that glorify what the Confederacy is all about. Visitors to the battlefield are not getting another message that balances that out unless they have really good educators.

Q: It can seem like the history of slavery has been completely erased from the battlefield. How did this happen?

Almost as soon as the war started to end, white Southerners began saying the war wasn’t about slavery. By the early 20th century, both the North and South were saying the war wasn’t about slavery. I think some of this came from the fact that white Americans, even the soldiers, didn’t want to think this incredibly devastating war that they sacrificed so much for on both sides had anything to do with anybody or anything Black. They wanted to distance themselves from Blackness as much as possible. Overall, it was willful exclusion—a very intentional effort to make sure the story of slavery and African American involvement isn’t part of how Americans remember what the Civil War was about.

As you know, there are not many Black visitors to the battlefield. The battlefield is predominantly white, too. There are probably some creative ways to think about how Gettysburg College could help change that. Gettysburg National Military Park would love to see more diverse groups of people out there.

Q: As a Predominantly White Institution (PWI) in Gettysburg, do we have more of an obligation to speak out about the role of slavery in the war? What—if anything—should the college do to tell the whole story?

The college uses these connections to the Civil War all the time which is fine (it’d be foolish not to), but there’s an obligation to speak about the role that slavery played in the war. For the most part, I think the college does a good job with that, but we can always do more. Taking other disciplines into consideration when talking about the war could have a more significant impact on how the story of the Civil War is told. The Civil War Studies program is supposed to be interdisciplinary, but it’s mostly been history. Tying in programs like Africana Studies, Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies or Public Policy could play an important role in how we think about Civil War history.

Q: How do we engage in meaningful conversations outside of our academic bubble?

Being in college comes with some responsibility. Part of that responsibility is communicating what we learn with others and finding ways to engage people in conversations outside of the classroom. It’s up to us to be co-learners with other people—especially people we disagree with. We need to treat people with respect and dignity, even if we think what they’re saying is completely wrong and even harmful. Figuring out ways to come alongside people we disagree with and saying ‘Okay, why do you think this and do you think it’s possible to think about this in a different way?’—I call it analytical empathy. I think we can empathize with people without having to agree with them. We don’t need to sympathize with them, but we can at least try to understand where they’re coming from.

Q: What do you wish students at Gettysburg understood or appreciated more about going to school here?

We stand on land that has a really deep, complicated history. A lot of the problems and challenges of American history played out here, and you can certainly say that about a lot of places, but it’s crystallized here. I think most students are aware of this, but not all of them fully understand the significance of going to school in a place where these intersections of history come together.

Q: In your video from the battlefield this summer you say: “We can all come to some sort of truth.” What does that truth look like for you?

I think there needs to be an understanding that all the losses of life during the war are tragic. Human life is incredibly valuable, so regardless of why they were fighting, the loss of that life is tragic. That loss also extends to the lives of the Black men, women and children who died before and during the war because of slavery. So on a macro level, I think that truth is rooted in understanding that regardless of whether you accept the bad revisionist history or not, it’s all a tragedy. That being said, it’s important we understand and accept that the organizing principle of the Confederacy was to protect slavery. If Africans never came to the shores of North America, there would be no Civil War. There might’ve been some other war, but we wouldn’t have had the same war. So that truth, for me, would look like acceptance. Acceptance that people on all sides do awful things. If we understand that truth, we could have a better understanding of how we got to where we are and function better as a society going forward. But if you accept lies and deny that truth, the problems we face are going to continue to fester.

This article originally appeared on pages 10 and 11 of the April 13, 2021 edition of The Gettysburgian’s magazine.

May 11, 2021

I am hoping the Visitors Center improves its messaging about how ending slavery was an essential part of preserving the Union . It’s doing a better job than in the past but there is much room for improvement.

November 14, 2021

Thank you for this important intetview. More work to do in understanding the civil war and it’s enduring legacy which prominently includes echoes of enslavement and terrorism.