Gettysburgian Investigation Finds Discrepancies in Textbook Prices Across Departments

Some classes at Gettysburg College are far more expensive than others (Photo Mary Frasier/The Gettysburgian)

By Anna Cincotta, Editor-in-Chief

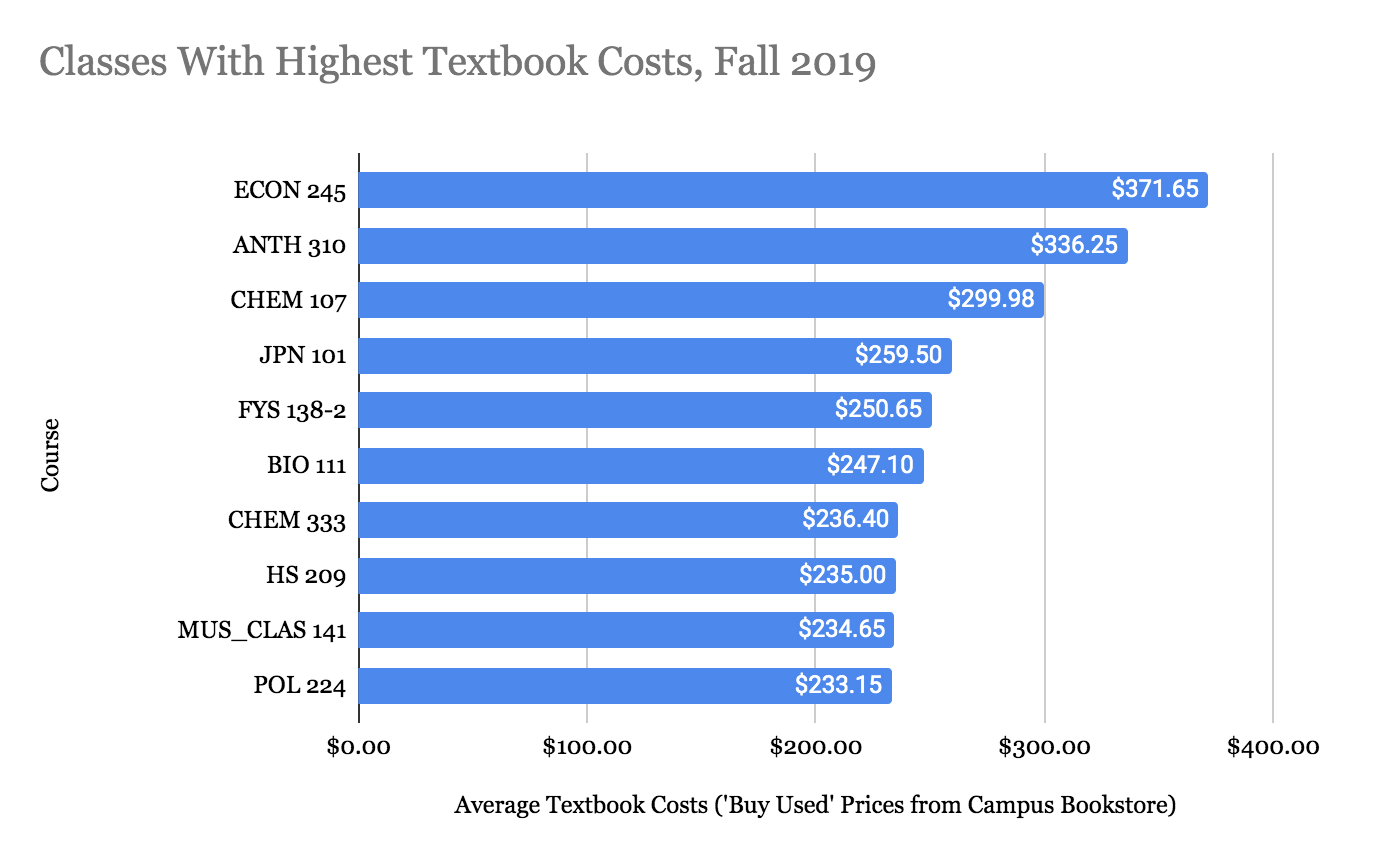

Any Gettysburg student who chooses to major or minor in chemistry must complete CHEM 107, or Chemical Structure and Bonding. According to data compiled by The Gettysburgian, more than 220 students took this course in the fall of 2019, and the cost of the required textbooks for this course, if they were purchased used from the college bookstore, amounted to $299.98, regardless of instructor.

Conversations about the cost of higher education in the United States usually turn to the skyrocketing tuition numbers affecting the accessibility of the undergraduate experience and promoting educational inequity. The average amount of debt acquired by student loan borrowers, according to the Federal Reserve, is now $32,731, and the annual cost of attendance at Gettysburg College eclipsed $70,000 after a 3.75 percent tuition bump was announced last summer amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Textbooks, however, are an expensive part of the undergraduate experience that are often left out of the “total cost of attendance” calculations made public by colleges and universities across the country. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that textbook costs are increasing by more than four times the rate of inflation. An interactive chart published by the government agency also shows that, while tuition increased by 63 percent between 2006 and 2016, the cost of college textbooks rose by more than 87 percent.

Gettysburg is no exception when it comes to high estimated textbook costs. Every year, enrolled students are expected to budget approximately $1,000 for “books and supplies,” according to a breakdown of annual costs of attendance on the college website. Textbooks are also considered an ‘indirect cost,’ and not factored into the total cost of tuition and fees.

“College already has a hefty price tag, and people forget that there are hidden costs from textbooks,” said Kate Delaney ‘21. “They create barriers for those who cannot afford them, and often low-price alternatives feel unacceptable for classes that require specific editions.”

A survey conducted by Musselman Library found that over 30 percent of Gettysburg student respondents spent more than $400 on books and other supplies, including materials like lab manuals and clickers, during the 2019 fall semester.

Last spring, library employees published an executive summary of this report which indicates that more than half of the student respondents who reported receiving financial aid did not have enough funding left over to cover course materials. The survey results also showed that over 68 percent of Pell Grant recipients—students with the highest financial need—shared that they were paying for their books out of pocket. About 15 percent of respondents stated that they had struggled academically due to their inability to acquire course materials, and almost a quarter of respondents reported not purchasing the required books for their classes because of cost.

Only 1 percent of students who responded to the survey indicated that they have not engaged in cost-saving strategies, like renting books from the bookstore or other sources and reselling course materials.

“I buy or rent my textbooks used through sites like Chegg and Valore because the Gettysburg bookstore, while convenient, is far too expensive for me,” said Emma Padrick ‘21.

Psychology major Rebecca Daly ‘22 also looks elsewhere in order to find more affordable course materials. “I tend to go for the cheapest options for textbooks,” Daly explained. “I also try to order early so I don’t have to worry about long shipping times, and use sites like ThriftBooks or secondhand sellers on Amazon.”

Our Investigation

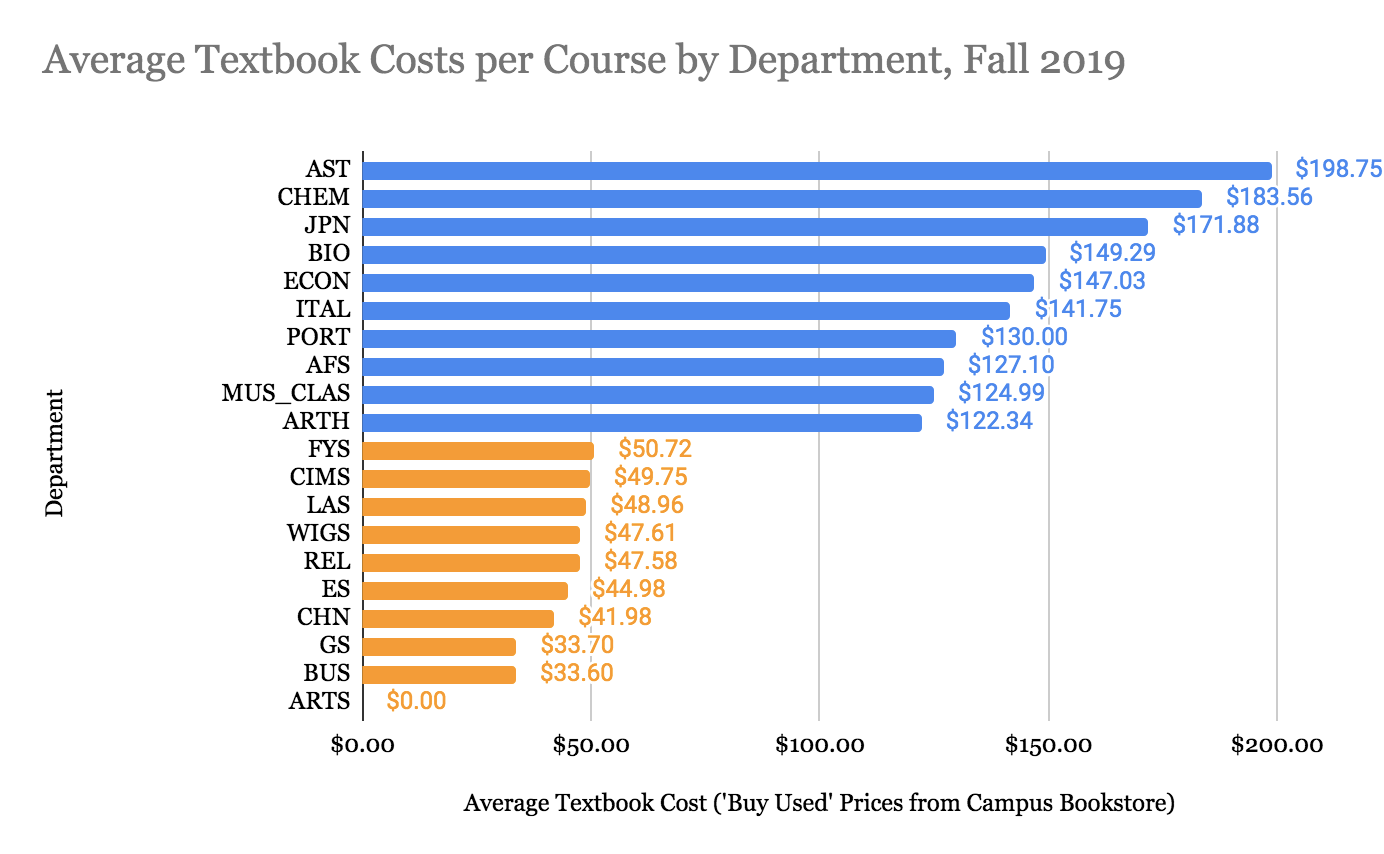

In response to ongoing conversations about equity and hidden costs during students’ undergraduate experiences, The Gettysburgian’s team of editors began an investigation into the cost of textbooks at Gettysburg College. After breaking down the costs of the assigned textbooks across courses through the website for the campus bookstore, we were able to calculate the average cost of textbooks in different academic departments on campus. Our team used the “buy used” costs of textbooks in the fall of 2019 in order to compile our data.

The investigation found that certain departments on campus were more cost prohibitive than others in terms of textbook prices last fall. The average cost of a textbook for an introductory astronomy course in the fall of 2019, for example, was approximately $199. In the religious studies department, however, students spent an average of $48 on course materials per class. The cost of required materials for a biology course? About $150. Meanwhile, German studies students were only spending about $33.70 per class, on average.

Padrick explained that she heard about high textbook costs prior to college, and researched cost-saving alternatives. Still, certain parts of the process were surprising.

“I was unprepared for how expensive some books were, and the disparity between disciplines,” she said.

“I do think more STEM-based majors are much more cost prohibitive,” added Delaney.

“As an English major, a lot of the textbooks I purchase are classic literature or stories that can be found for very cheap or are even open access,” she continued. “I don’t spend nearly as much on textbooks as my roommates, because although I often have to buy more books, they are not as costly as most textbooks are.”

Assistant Dean and Director of Scholarly Communications Janelle Wertzberger, who fielded the textbook costs survey last fall, explained that the disparities in textbook costs across departments might be indicative of the cost of introductory course textbooks, which are often quite expensive in STEM and social science classes.

“At the introductory level across the board, but especially in the sciences and social sciences, you will find expensive textbooks,” she said, citing last fall’s survey findings. “I think, in general, STEM classes—and a lot of classes at the 100-level—are more expensive classes than classes students take later on.”

This makes courses more cost prohibitive for first-year students, who often enroll in multiple 100-level classes when they arrive on campus. Last year’s report also shows that they spend more on textbooks than students in the sophomore, junior, and senior classes.

Currently, the campus bookstore at Gettysburg College does not make the “book list” data, which consists of every book assigned each semester, available to Musselman Library staff. This complicates the picture for instructors and students, in that it often results in students spending money unnecessarily, particularly if they’re comfortable with reading a digital version through the library. Wertzberger explained that the ISBN numbers contained in the “book list” allow librarians to cross-check the library database and see how many assigned books they already have in their collection, while also providing the information they need to run the numbers through the library vendors database. This process lets them know if they can purchase some of the materials and make them free for students.

“Now there are some big exceptions there,” Wertzberger said. “STEM textbooks are really expensive, but those books are never available for library eBook licenses. The publishers don’t sell them that way because they recognize very clearly that it’s a revenue stream for them.”

Still, Wertzberger expressed that students will often spend money on books that are available for free as digital eBooks because professors are not aware that they are a part of the library’s collection.

Professor Perspectives

The good news about textbook costs, specifically, is that solutions lie largely in the hands of college faculty who assign required reading materials for their courses. Open Educational Resources (OER) provide students with more opportunities for academic success free of charge. Research from the University of Georgia in 2018 also found that students with greater financial need see the most benefits from OER when it comes to measuring academic success.

“The cost of tuition is outrageous,” said Wertzberger. “You can’t change that as a professor, but you can change what your books cost—that’s within your control.”

And moving to OER is “really doable,” according to Vice Provost and Dean of Arts and Humanities Jack Ryan.

“It just requires a little legwork,” he added.

This legwork might involve reorganizing a course’s structure around a new textbook, for example, or being more flexible about the books assigned for a course if they result in similar learning outcomes for students. Instructors at Gettysburg across all departments have access to zero-cost and low-cost materials made available through eBooks, the library’s digital reserve, and open educational resources on websites like OpenStax—an educational initiative at Rice University with peer-reviewed, openly-licensed textbooks.

“We have to continue to promote open source materials, and I know that the technology is out there to deliver course content in a much more effective way,” Ryan said. “There’s no reason why you can’t use digital documents in any class.”

Political Science Professor Bruce Larson explained that he decided to move to an open access textbook this year for his introductory American Government course after becoming uncomfortable with the notion of assigning costly reading materials. He didn’t want to be responsible for putting additional financial strain on families—especially during a pandemic.

“If I’m spending my own money that’s fine, but in a way I’m spending for students—and that’s when it hit me,” he said. “It’s so strange that I’m controlling the market. All of a sudden I got really uncomfortable with that.”

Larson added that the open source textbook he’s using this semester through OpenStax is high quality and achieves his learning goals. He plans to use it when he teaches American Government next year in order to continue eliminating book costs for students who enroll in that 100-level course. Still, Larson noted that it’s more difficult to find more comprehensive texts that are open access. “If you’re going to use a textbook for a class, that’s what’s hard to find,” he said.

Other professors have voiced concern over the quality of open access materials, and particularly textbooks.

“I have reviewed some OER materials,” said Associate Professor of Economics Brendan Cushing-Daniels. “They’re okay if not great.”

He added that bigger publishing companies tend to have “more resources to spend and deeper market penetration” that allow them to “pay for high-quality graphics and illustrations.” Still, he noted that moving to low-cost and zero-cost classes is an important goal moving forward, and that professors should learn from colleagues who have successfully made the switch to more affordable course materials.

Associate Professor of Environmental Studies Andy Wilson also indicated that he’s wary of the quality of open access materials for introductory classes.

“I’m afraid my experience with open access textbooks is that they simply aren’t as good as the costly alternatives,” he said. “They are updated less often, if at all, and are generally less in-depth.” Wilson, like Cushing-Daniels, also noted that the graphics “are often terrible—which is a shame because STEM texts rely heavily on images.” Still, since he teaches more upper-level classes, he has found it easier to rely on alternatives like peer-reviewed articles to keep costs down.

“There are more than enough [open access resources] for elective classes,” Wilson said.

Contextualizing Open Education: The COVID-19 Pandemic

Ryan hopes that, given the uncertainty surrounding the pandemic and the abrupt instructional changes that forced many members of the faculty to engage in developing new technological skills, there will be more movment toward open source materials for their courses.

“I’m not sure that COVID is going to be the root cause of a lot of these changes, but one thing the pandemic did do was disrupt the normal approach to things,” he said.

Wertzberger added that the pandemic and subsequent move to remote instruction last spring highlighted the reasons why she’s dedicated time and energy to ensuring the affordability of course materials for students.

“COVID-19 really laid bare the inequities and discrepancies that were always there,” she said. “I do the work I do in open education because I think that it will fix the problem and its root.”

Instructors who had already adopted open sources for their classes were more prepared last spring during the move to remote instruction—that is, all of their students could continue learning with the same course materials. Meanwhile, students who relied on library reserves because of affordability concerns when it came to buying expensive textbooks were left without the resources to succeed academically during remote learning, placing them at a distinct disadvantage.

Incentivizing the Use of Open Educational Resources

In an effort to encourage part-time and full-time members of the Gettysburg College faculty to make the move toward zero and low-cost classes, Musselman Library and the Johnson Center for Creative Teaching and Learning teamed up to provide grant opportunities for individual instructors who adopt open access materials, starting at about $500.

“The real incentive would be to reward instructors for doing this [open education] work in the tenure and promotion system,” Wertzberger said. “Whatever is rewarded will be done, so if adopting an open textbook counted in the scoring for tenure and promotion, you better believe a lot more people would be doing it.” This change, if applied to the tenure and promotion process, would be structural, according to Wertzberger, and could result in real transformation when it comes to textbook affordability at Gettysburg College.

More access to quality open access textbooks would also make it easier for professors concerned about learning outcomes to adopt more affordable materials.

Putting students first was also cited as a reason to prioritize OER.

“Income inequality has grown substantially in the United States, and we can’t have this group of kids who can’t afford books,” Larson said. “We’re not going to be able to thrive as a country—we have to do our part as professors, and that’s an incentive.”

Gettysburgian staffers Ben Pontz, Garrett Adams, Nicole DeJacimo, Phoebe Doscher, Lauren Hand, Carter Hanson, Gauri Mangala, and Katie Oglesby contributed to data collection for this story.

This article originally appeared on pages 4-8 of the March 16, 2021 edition of The Gettysburgian’s magazine.

March 22, 2021

An assistant dean of the College acknowledges our loud that the cost of tuition is “outrageous”…that seems pretty unusual and newsworthy in and of itself. Like a gaffe in politics…where one unwittingly says the truth.