Richardson Event Traces the Rise of Digital Propaganda to Political Cults

By Ella Prieto, Managing Editor

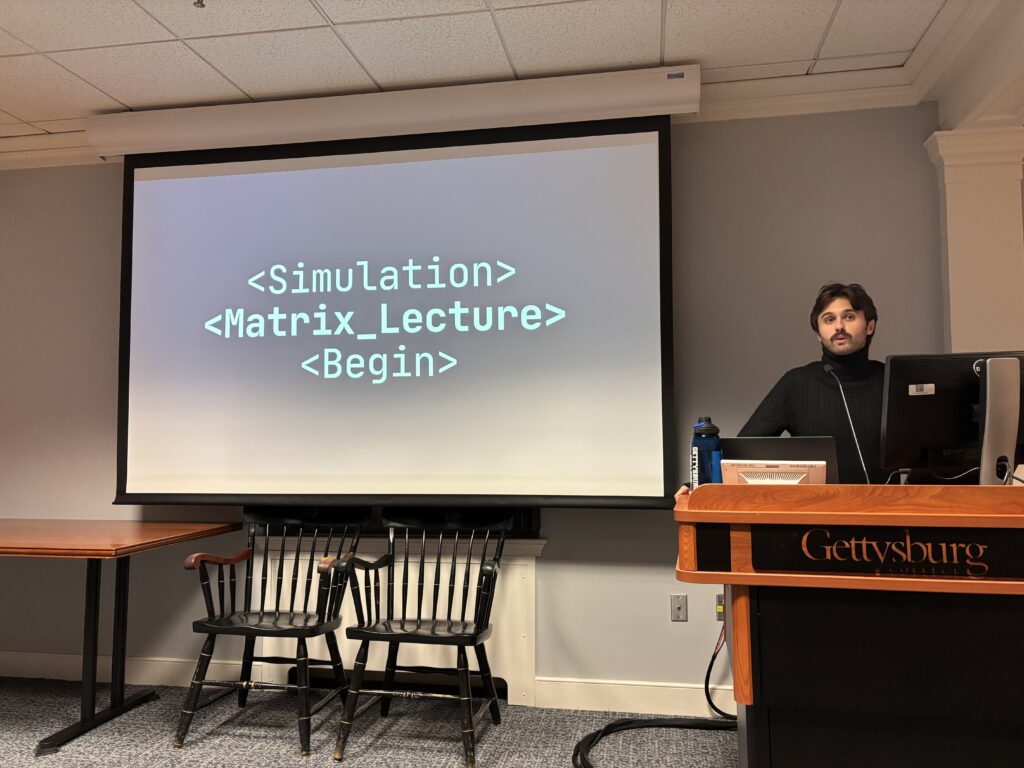

On Tuesday, Nov. 19, alumnus Thomas Cassara ’23 presented at the Richardson Event in the Pennsylvania Hall Lyceum. His speech, titled “May the Matrix Guide You: Online Political Cult Formation in the Digital Age,” traced the rise of propaganda throughout the world.

Cassara began with a brief history of propaganda, divided into the pre- and post-printing press periods. In the ancient world, propaganda was achieved through rudimentary means, such as architecture, coins, poems and armor.

“You might not think of coins as being a form of propaganda,” he remarked. “But if the guy in charge is printed on your gold, every time you act as an economic actor, it inspires at least fear, maybe even loyalty.”

This type of propaganda persisted until the invention of the printing press, which enabled the Protestant Reformation. Utilizing the press, protestants directly marketed to their audience, emphasizing a personal relationship with God, thus opposing traditional authority, and initiating open access to the Bible by printing it in languages other than Latin. This early form of targeted marketing heightened over the following centuries.

Cassara then jumped to 1896, a year of massive leaps for communications technology. To begin, Lord Northcliffe created the Daily Mail, popularizing the practice of yellow journalism where news organizations focus on selling papers via sensationalism rather than a commitment to the truth. Then, Lumiere produced the cinematograph, achieving an easier way for audiences to connect to stories. Finally, Guglielmo Marconi constructed the wireless telegraph, a technology that could directly enter people’s homes allowing for consistent access, leading it to the favored tech of twentieth century propaganda. These technologies are then combined into one with the invention of the television.

“Journalism is done more effectively [on televisions] at times than in print,” said Cassara. “You’re able to watch radio shows on television, and you get the power of cinema at home. All of these prior technologies are distilled into one powerful tool of the television.”

Audiences who witnessed historical events such as the Kent State massacre, the fall of the Berlin Wall and the 9/11 terrorist attacks on their television screens were more impacted by the events than if they would merely read or listened about them. Furthermore, it had a unique power in its ability to swing political outcomes through coverage. The internet then took this power to the next level.

With the rise of the digital age, new forms of recruitment were born via private communication apps, social media, games and gaming mods. Starting with gaming, Cassara broke down how they provide an easy recruitment tool for political extremist cults.

“They’ll [extremists] go into matchmaking lobbies and throw in slurs to try to get attention and then anyone that they can sort of draw in a little bit, they offer to go into a private discord server and that’s how they draw them in,” he explained. “They will jump into the mainstream and pull people down the river.”

Additionally, video games allow players to control avatars engaging in acts of violence, sometimes personal fantasies. Avatars can also wear explicit outfits, and extremists have made their own mods to allow for Nazi gear.

Social media is also an easy recruitment tool through targeted ads and posts designed to manipulate algorithms. Furthermore, social media allows those who are bought into movements to rage on social media. Cassara explained that this “makes [people] feel better in the short term but drums into a greater sense of unease in the long term.” This, combined with the sustained spread of conspiracy theories and extremists’ marketplace power through merchandise, makes social media ripe with political cults.

What also differentiates the Internet from past technology is its physicality, which draws users in and raises the consumption rate.

“There is something more participatory about interfacing with a physical object that allows you to access a nonphysical realm that the other forms of propaganda cannot give you,” said Cassara.

This high rate of consumption leads to a plethora of issues. Cassara cited Adam Seagrave’s 50/50 problem: “More than 50% of Americans spend more than 50% of their waking hours living in virtual, artificial worlds rather than the created one in which their bodies exist. The 50% threshold represents a tipping point that renders dialogue, deliberation, civic friendship and compromise extraordinarily difficult in any society.”

Such a high rate of time online creates private worlds for users when they are constantly manipulated and propagandized. Cassara provided statistics that exemplify this, such as a 2018 PEW Research Center study that found 90% of teens in the United States say they play video games on a computer, game console or phone. Another study measured that Americans aged 16 to 24 years old spent seven hours and 23 minutes on internet-connected devices daily in 2023.

“We are increasingly going into these private virtual worlds, and we’re losing sight of the world around us in a way that previous propaganda devices did not have the power,” stated Cassara.

Additionally, decentralized tactics used by extremists makes them more isolated and dangerous. This, along with the plethora of apps they can utilize, makes groups hard to track. Cassara argued that these political cults also disprove Joseph Goebbels’ “sixth principle” of Nazi propaganda, which states that propaganda has to come from a central authority to be effective. Political cults online operate in a decentralized fashion yet have been able to powerfully distribute propaganda, effectively hide from law enforcement and communicate across long distances.

Cassara then examined how political cults often operate in ways similar to religion, especially sharing traits with the Protestant Reformation. They utilize new interpretations of scriptures, employ martyrs, saints and leaders, and promote “good works” and apocalypse imagery.

Cassara concluded his presentation by discussing techniques that can be used to “navigate the matrix.” The default response for many platforms has been censorship, though this has only resulted in mixed success, as groups often just jump from one social media platform to another. Instead, Cassara believes that this effort should start in the classroom, with the implementation of media literacy, science, and philosophy education to enhance critical thinking. Community-building is also key to deradicalization.

“My advice is to build community wherever you can, and please be patient with your friends and loved ones who are lost down the rabbit hole,” he said.