By Vincent DiFonzo, Content Manager

(Poster Provided)

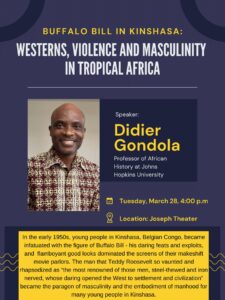

On Tuesday, Professor Didier Gondola of Johns Hopkins University visited Gettysburg College to give a lecture entitled “Buffalo Bill in Kinshasa: Westerns, Violence, and Masculinity in Tropical Africa.” The lecture began at 4 p.m. in Joseph Theater.

Professor Gondola specializes in African History and holds a Ph.D. from Paris Diderot University. His research interests are popular culture, African diaspora, gender and post-colonial issues. Publications of his include “Frenchness and the African Diaspora: Identity and Uprising in Contemporary France” and “Postcards from Congo.”

The lecture began with an introduction from History and Africana Studies Professor Abou Bamba, who detailed Gondola’s credentials and career achievements.

Gondola introduced himself and explained that his lecture is based on his 2016 publication “Tropical Cowboys: Westerns, Violence, and Masculinity in Kinshasa.” Gondola began by discussing Buffalo Bill, whom the lecture is named after.

Gondola explained that Buffalo Bill was a “legend” of the American West who “shaped masculinity and this idea of how to be a man” in the Belgian Congo in the 1950s. Buffalo Bill was a frontiersman, buffalo hunter and performer who became famous as an entertainer throughout the world. He put on elaborate cowboy-themed shows and “took America and Europe by storm,” according to Gondola.

Gondola stated that Buffalo Bill “single-handedly transformed the image of a cowboy from an outlaw to a hero.”

However, Gondola said that Buffalo Bill was no saint, nothing that “many of his admirers sweep under the dirty rug of history that he contributed to the slaughter of over 50,000 buffalo” and “contributed to the demise of Native American tribes.”

Despite this, he was so famous that he performed for figures such as the Pope and Queen Victoria.

After introducing Buffalo Bill’s background, Gondola gave a brief overview of the history of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

What now forms the nation of the Democratic Republic of the Congo was once a Belgian colony before gaining its independence. King of Belgium Leopold II reigned from 1865 to 1909, and he ruled the Congo as his personal possession.

Gondola explained that Leopold “never set foot there, but profited greatly” from his exploitation of the Congo. Leopold oversaw a “reign of terror” in the country, as Gondola described it, in pursuit of rubber.

Local Congolese people were forced by Belgians to meet rubber quotas or the Belgians would kidnap the women and mutilate the hands of children. The Belgians used the people for slave labor and severely punished anyone who dissented.

In 1908, Belgium took direct control of the Congo as its colony. This began a 50-year period in which Belgians attempted to Christianize and “civilize” the country. Gondola explained that the Belgians believed they were given a “God-given mission to save Africans from savagery, and to domesticate their space, bodies, and minds.”

Belgian Catholic missionaries took charge of education, Evangelization, sports, medicine and other vital activities of the Congo. In order to further spread their message, they turned to filmmaking.

Gondola stated that the film could “easily appeal to Africans, reach a wider, younger audience, and spread religious ideas” to the Congolese.

However, European films shown to the Congolese were often demeaning. Gondola provided examples of these films, including long documentaries that explained how to be punctual and how to use items such as a blanket or wheelbarrow. Naturally, young Congolese boys hated these films.

“People in Kinshasa didn’t want to watch them,” explained Gondola.

Buffalo Bill’s films were soon introduced to the Congolese, and these films quickly appealed to the youth of the Belgian Congo. These movies depicted the American Wild West and violent encounters between so-called “cowboys” and Native Americans. Gondola detailed how cowboys were glorified and Native Americans were depicted as savages. Nonetheless, these films appealed to the young men of the Congo, who were searching for meaning in their masculinity.

“These movies allowed young boys to create their own definition of masculinity,” said Gondola.

Gondola theorized that the Belgians liked Buffalo Bill because of the similarities between him and King Leopald II.

“In the eyes of Belgian Catholic missionaries, both figures tamed the wild and advanced European civilization,” said Gondola.

Gondola pointed out that Belgians, for many years, celebrated their Independence Day with elaborate Buffalo Bill shows. Gondola described how these movies were also iconic to the young people in Belgian Congo’s capital, Kinshasa. However, they also encouraged violence.

“In those theaters that were controlled by the missionaries and later on in their own makeshift theaters, young people watched the movies with a lot of excitement. People were screaming, people were fighting, it was really crazy,” explained Gondola. “When they were watching these western movies, they were not rooting for the Native Americans, even though they themselves were oppressed.”

Gondola described how the Congolese did not relate to the Native Americans or saw themselves as in the same situation. They related to the cowboys, leading to the glorification of Buffalo Bill and figures similar to him. The youth wanted to watch a violent expression of masculinity.

“Dialogue didn’t matter, it was the action that mattered,” Gondola said.

Gangs in Kinshasa began to refer to themselves as “Bills.” Gondola explained how these gangs participated in “magic rituals” that were thought to increase the strength of a man. These included “kintulu” (bodybuilding) and “kamo,” which refers to the practice of allowing an older “bill” to cut you with a razorblade and burn your open wound.

Gondola called these rituals “self-destruction and self-preservation at the same time.”

With the creation of these gangs, violence hit the streets of Kinshasa. Gangs were fighting over turf, girls and nicknames. Gondola described the gang culture as very sexist. There were more men than women in the Congo at the time, which led to gangs viewing women as trophies. A culture of “collective rape” formed around these gangs, and the women who lived in a specific gang’s turf were targeted, kidnapped and raped by rival gangs.

A language called Indoubill was developed to “conceal” these dark actions by the gangs.

“Fifty percent of the vocabulary of the language involved drugs or girls in some way,” Gondola said.

Gondola then explained how the Buffalo Bill subculture also had an impact on the decolonization process in the Congo. Bills participated in the Léopoldville riots of January 1959, putting pressure on the Belgian government to free their colony. Before the bills had formed, the Belgians had no intention of letting go of their control over the Congo.

“If it weren’t for the Bills, I don’t know if the Congo would have gained independence when it did,” said Gondola.

Gondola concluded his lecture by sharing that many former Bills members went on to gain important government roles, such as the Congolese Ambassador to the U.N. and the Governor of Kinasha.

Gondola then took audience questions.

History Professor and Chair of the International and Global Studies Program William Bowman asked about the impact of Pan-Africanism among the Congolese youth. Gondola explained that due to “rudimentary” schooling and other preventative factors, Pan-Africanism did not become popular among the Congolese at the time.

Another audience member asked about the modern memory of the Bills and if they are remembered with nostalgia or stigma. Gondola explained that the Bills are remembered positively, and he discussed the modern desire for strength in Kinshasa.

He added that there is immense nostalgia among former Bills today. However, when asked about the Bill’s association with sexual violence, Gondola explained that most former Bills deny their participation in those acts.

The event concluded with brief remarks from Professor Bamba thanking Professor Gondola and the audience for their time.