Introduction

By Nicole DeJacimo, Managing Editor

The COVID-19 pandemic, an overall decline in enrollment and mass resignations have all contributed to Gettysburg College’s recent financial challenges. In 2021, Gettysburg College ran a $6.7 million deficit caused by a significant decrease in operating revenue. At the same time, net assets grew by $79 million, $75 million of which came from growth in endowment investments, according to the 2021-22 Factbook. Additionally, Gettysburg is facing significant staff shortages, particularly in dining services.

Gettysburg’s deficit mirrors a decrease in revenue for many liberal arts colleges throughout the North East since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Bloomfield College in New Jersey, among others, risks closing its doors to prospective students. Other institutions have merged with or been bought by larger universities. Boston College, for example, recently bought Pine Manor College in Massachusetts.

The National Student Clearing House reported that one million fewer students are enrolled in a college or university relative to before the pandemic. According to the 2021 Fact Book, 17.8% of accepted students enrolled at Gettysburg College. That has steadily declined since 2012, when 34% of accepted students decided to enroll. To counteract this, the College admits a higher rate of applicants, increasing the acceptance rate. In 2018, Gettysburg admitted 45.4% of applicants; in 2021, the College admitted 56.3%. According to Executive Director of Communications & Marketing Jamie Yates, the College plans to purposefully decrease the future student population, lowering the admissions rate and guaranteeing on-campus housing for all students.

Gettysburg’s Financial Situation

By Carter Hanson, Magazine Editor

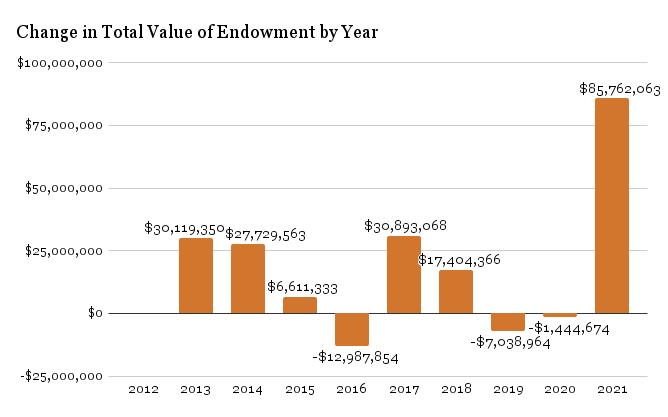

Between 2020 and 2021, Gettysburg College’s endowment grew from $322.7 million to $408.5 million, an increase of $85.8 million, according to the 2021–22 Fact Book. This leap in the value of the College’s investments stands in stark contrast to the growth of the endowment in the recent past: between 2019 and 2020, for example, the endowment decreased by $1.4 million.

Why the sudden improvement in the value of the endowment? According to Economics Professor Brendan Cushing-Daniels, the growth of the endowment reflects the growth of the U.S. economy as it rebounded from the initial shock of the COVID-19 pandemic. “If you just go back and look at what the S&P 500 did over that same period, you’ll see a big jump there as well,” said Cushing-Daniels. “You’d be shocked if the vast majority of that is not just growth in the value of our assets.”

Of the $85.8 million increase in the value of the endowment, $78.3 million is profit from market performance, while the remaining $7.5 million comes from donations, which, according to Associate Vice President for Finance Chris Delaney, is “about the average over the past 10 years.” At the same time that the endowment is growing at the highest rate since Gettysburg began publishing endowment information a decade ago, the college is facing a steep decline in operating revenue. During the same period that the endowment grew by $85.8 million—between 2020 and 2021—the college ran a deficit of $6.7 million, as revenue from tuition, room and board decreased by a total of $26.4 million.

This deficit was caused by the dramatic reduction in room and board revenue as Gettysburg transitioned to virtual learning during the first waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring and fall semesters of 2020. Spending also increased when students returned to campus as the College introduced a testing system, purchased personal protective equipment (PPE) and erected large tents for outdoor class.

“COVID was the main driver for 2021’s performance,” said Delaney. “Hopefully that deficit was a one-time event.”

Compounding the challenge of addressing the COVID-19 pandemic is the gradual shift in demographics across the country, making it more difficult for Gettysburg to find prospective students.

“Higher education in general is facing … strong financial headwinds for a whole bunch of reasons,” said Cushing-Daniels. “There are fewer kids going to college in the next couple of years. Where those children live and where our typical strong recruiting market is— those are in different places, by and large. So for a whole bunch of reasons the cash flow on a year-to-year basis is endowment is severely limited.

“We are restricted by both the gifts themselves— when people give large gifts they typically restrict it to something: ‘I want to give to scholarship,’ ‘I want to give to this building or that building,’” said Cushing-Daniels. “And then we’re also restricted by law facing some challenges.”

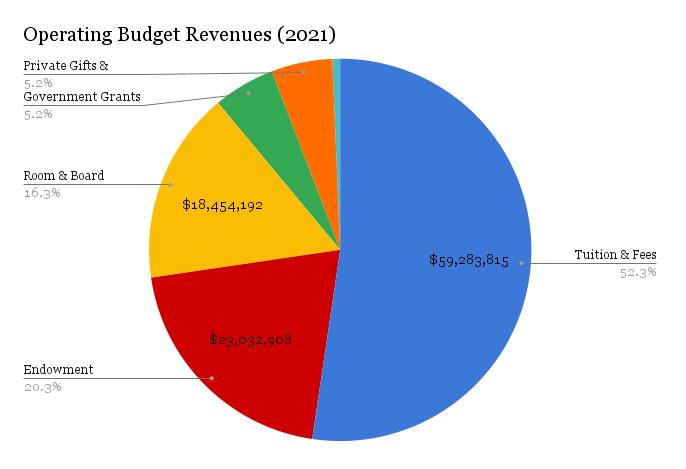

While Delaney expects tuition, room and board revenue to rebound now that the high tide of the COVID-19 pandemic is likely past, demographic changes pose a long-term challenge to Gettysburg’s financial health. Tuition and fees, as well as room and board, are critical for the year-to-year maintenance of the College, as they accounted for approximately 75% of annual operating revenue in 2021.

After tuition, the endowment is the second most important source of revenue, providing about 12% of annual operating revenue. Although the recent growth of the endowment helps the College address the challenges of maintaining a stable budget, spending from the in how much we can roll off the endowment into the operating budget.”

About 75% of the endowment is restricted by donors to be used for specific purposes, such as scholarships, endowed professorships and the Sunderman Conservatory. However, 76% of the endowment is intended for “general institutional support and scholarships,” according to Delaney. This means that although most of the endowment is donor-restricted, it is still “budget relieving,” and can be used to supplement decreases in operating revenue.

Furthermore, Gettysburg’s approach to recent fluctuations in the legal limit on endowment spending may indicate that the College is more financially healthy than it may first appear to be. Gettysburg limits its annual endowment spending to about 5% of the “pooled endowment,” which is a large subset of the endowment that the College has the most direct control over in terms of how it is invested. This 5% limit is set by law, as Gettysburg is a not-for-proft institution. In 2020, however, this legal ceiling was raised to 10% for the years 2020, 2021 and 2022 by the Pennsylvania government, in order to allow institutions to recover quickly from COVID-19.

In order to compensate for the drop in revenue from tuition, room and board in 2020, Gettysburg increased their endowment spending rate to 10%. However, this has since returned to 5%, despite the legal allowance to continue higher spending until the end of 2022, indicating that Gettysburg remains fiscally resilient.

The Great Resignation

By Phoebe Doscher, Editor-in-Chief

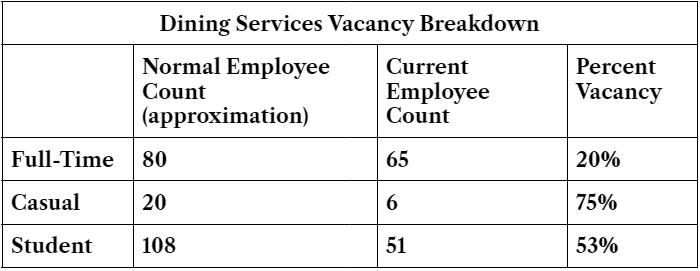

In mid-January, Gettysburg College reported that approximately one in six of all staff positions were vacant, particularly impacting Dining Services and Facilities. Dining Services is operating with only 50% of their normal staff, which comprises full time, casual and student employees.

Vacancies & Recruitment

Both Facilities and Dining Services reported a significant decrease in their applicant pools in the past year. Te lack of applicants has caused problems in the day-to-day operations of both departments. “Like many businesses in the area and nationally, we have been faced with the challenge of finding staff to fill some of our vacant positions,” said Associate Vice President of Facilities Planning & Management Jim Biesecker. “We have noticed a significant reduction in the applicant pool for the vacancies we have. Tat has impacted our ability [to] hire replacements.” In January, Director of Auxiliary Services Mike Bishop said he received fewer than 10 applications and six full-time workers departed in the two previous months. In mid-February, three full-time workers quit over the course of three weeks to take higher-paying jobs elsewhere. Some have left because they do not want to adhere to the masking requirement while others are worried about being exposed to COVID.

“This staffing shortage is a huge problem for us and many businesses around town,” said Bishop. “We do not have the luxury of being closed on days when we are short staffed, like most of the restaurants in town that close on Mondays and/or Tuesdays.”

Dining Services has noticed the greatest loss in casual employees, or on-call employees who work as needed, with 75% of those positions currently vacant. There is also a shortage of student employees; Dining Services typically employs a total about 108 students, while they currently employ only 51.

“Our student applicants have been very low… and many applicants only want to work four to eight hours a week,” Bishop said.

Student worker Seamus Meagher ’23 works eight hours a week at Bullet, typically in the Higher Bred sandwich line. He went abroad in the fall, and has returned to find changes due to shortages this semester.

“Since coming back to work, it is evident that the lack of employees is causing issues,” said Meagher. “Something that has happened is certain sections of Bullet have had to close early or not be open at all. This can make work more difficult, especially when students get annoyed and act difficult when ordering.”

During the spring semester, Bullet has frequently closed the Root salad bar and Pi, which prepares made-to-order pizza and pasta, for days at a time due to staffing shortages. In October, the Dive, a dining option located in the Jaeger Fitness Center, also shuttered as a result of staff shortages, and starting Feb. 13, Bullet began closing at 10 p.m.

“There’s not a lot of people that come from 10 to 11 p.m.,” said Retail Dining Supervisor Amy Ellicot. “Shutting down at 11 p.m. gave everybody just a half an hour to get the whole place shut down. Now with closing at 10 p.m., even with a few people, in that hour and a half they can get everything done efficiently.”

The vacancies within Facilities are not isolated to one area. Associate Vice President Jim Biesecker said there are shortages in their housekeeping, mechanical trades and grounds department divisions, in addition to their manager and supervisor team.

“Since the vacancies are distributed across the different parts of our operations, we are able to adjust schedules and services to help provide adequate campus coverage,” Biesecker said.

Without consistent employees, the Facilities department combines schedule adjustments, contractor support and overtime work to account for the losses. They have also implemented new equipment options to make work more efficient and allow them to shift responsibilities in lieu of workers.

“Staffing shortages do have an impact on the staff within an organization. Some of our services involve covering vacancies of a position that might have a daily building assignment,” said Biesecker. “This is a similar process we use when covering [employees’] jobs during vacations and other absences, but on a more consistent basis.”

National Trends

The staffing shortages at Gettysburg are not a unique problem. The U.S. Bureau of Labor reported that 4.3 million Americans quit their jobs in December 2021. These departures are considered part of “The Great Resignation,” which accounts for over 30 million individuals who have left their jobs since spring 2021.

“Nearly every organization throughout the nation has been impacted in some capacity, colleges and universities alike. Our experience mirrors broader trends,” said Executive Director of Communications & Marketing Jamie Yates. “We have taken important strides to adapt to an evolving work environment and to improve recruitment and retention of employees.”

In response to the shifting workforce, the College began offering a Voluntary Separation Incentive Program (VSIP) for eligible administrators and faculty members, but did not include support staff due to vacancies. Instead, the College chose to raise wages for hourly workers to incentivize them to stay and apply.

President Bob Iuliano announced that effective March 11, the College will be raising its starting minimum wage to $15 an hour for benefits-eligible hourly employees who work 20 hours or more per week. Student employees are ineligible for this raise, and their pay will remain at $8 per hour. Adjustments to wages and benefits for eligible employees will be allocated progressively, and account for wage compression. The lowest-paying jobs will receive the largest increase in pay. The College plans to provide benefits-eligible support staff a 2% increase at least in fiscal year 2022.

The last time the College raised the starting minimum wage for hourly employees was in mid-November 2021, when they raised the pay from $11 to $13. Te College is also hosting a job fair on March 5 at the Majestic Theater to encourage job-seekers from the Gettysburg community to apply for part- and full-time positions.

The Path Forward

While Dining Services and Facilities face staffing shortages, the campus community will continue to see the impacts in daily operations. From long lines at Bullet to closures throughout campus, staff shortages will continue to have a profound impact on student life for the foreseeable future.

“I think it’s just important to remember to be patient with the workers,” said Lillian Newton ’23, a student worker at Bullet. “The non-student employees are working really hard and spending long days trying to make sure we can be open and running as smoothly as possible, which makes it possible for the student employees to have a good environment to work in.”

Dining and Facilities plan to continue working with Human Resources to recruit applicants amid the shifting workforce.

“I see the things that other schools are doing, and they’re trying to make it work for the people that they have and make a great experience for the students,” said Ellicot. “[Dining Services has] had pretty high rankings over the years and we want to continue that. We’re doing the best we can.”

This article originally appeared on pages 6–11 of the February 22, 2022 edition of The Gettysburgian’s magazine.