Gettysburgian Investigation Finds Broad Disparities in Department Course Enrollment

By Benjamin Pontz, Editor-in-Chief

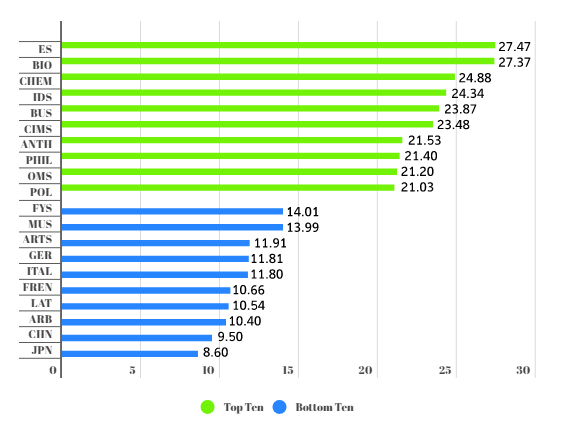

Gettysburg College advertises an average class size of 17. But, depending on what subject a student majors in, they may rarely—if ever—see such a class size. An Environmental Studies course, for example, is five times as likely as an English course to have an enrollment above the college average. An Organization & Management Studies course is twice as likely as a Theatre Arts course to have an enrollment above that benchmark of 17. The average enrollment for a course in Biology is over 27, while the average for a course in the Sunderman Conservatory of Music is below 14.

While specialized equipment, the nature of foreign language instruction, and the necessity to offer capstone courses even in departments with small numbers of majors can require certain classes to have smaller enrollments, broad disparities still exist between disciplines and divisions of the academic program in terms of the size of course enrollments and the number of students faculty members are expected to advise.

The Gettysburgian compiled a dataset containing an entry for each of the more than 4,200 full-credit lecture sections offered at Gettysburg College over the past four years. That data shows that, on average, courses in the natural sciences (a division that includes psychology, computer science, and mathematics) have the largest enrollments, followed by social sciences and interdisciplinary programs, and finally the arts and humanities, which have the lowest course enrollments. All told, 12 subject areas have average class sizes above 20, while, at the other end of the spectrum, 11 subject areas have average class sizes below 12. In other words, to a large extent, the size of your classes will depend on what you choose to study.

Download: Summary table with average departmental course enrollments (PDF)

To Professor of Political Science Bruce Larson, the department chair, that disparity is a problem.

“We make a promise to these students who come to liberal arts school because they want small classes,” he said. “And when we don’t [deliver] this reputation gets around and we can be damaged by it.”

Explore: How we reported this story

Some classes are expected to have fairly high enrollments. Astronomy 102, for example, which many students take to fulfill their lab science requirement, has an enrollment cap of 40, a benchmark that is fairly standard across introductory courses in the natural sciences.

Biology Department Chair J. Matthew Kittelberger said that high enrollments in the sciences are not necessarily a problem because students still receive individualized attention in labs.

“[M]uch of the in depth education occurs in small lab settings,” he said.

[wpdatatable id=1 table_view=regular]

Download the full dataset in CSV form (free to reuse with attribution)

In other disciplines, however, department chairs do worry about large introductory courses.

Dr. Amy Evrard, who chairs the anthropology department, in which the average class size for an introductory course is 28.2, said that she worries about first-years not having accessible, full-time faculty members with whom to build relationships.

“Where the burden comes for us is in the teaching and making sure we can offer enough 100-level courses to meet student interest,” Evrard said. “We end up having to rely on adjuncts, which we think is problematic.”

She added, “Data shows that adjuncts are not as available and invested as full-time faculty, meaning that students are being shortchanged.”

On average, faculty members who do not have tenure and are not on a tenure track teach courses that are 12 percent larger than their tenured and tenure-track peers. In total, 37 percent of Gettysburg courses are taught by adjunct, visiting, or other non-tenured, non-tenure track professors, and those courses are primarily at the introductory level, and tend to have the largest enrollments.

Associate Professor and Chair of Environmental Studies Salma Monani said that she and her colleagues do worry about the student experience in these types of classes, noting that the size “just limits the things you can do,” such as taking field trips. She said that she and her colleagues try to use active learning pedagogical techniques to ensure that even the larger classes have the feel of a Gettysburg course.

Beyond the 100-level, course caps tend to decrease, but they can vary dramatically by department from as low as seven or eight in some 300 and 400-level seminars (and 200-level art studio classes) to as high as 36 in natural science courses, many of which are broken into smaller subsections through labs.

In some departments, though, classes are consistently overenrolled relative to their caps. During the four-year period analyzed, nine departments had more than one quarter of their classes over capacity.

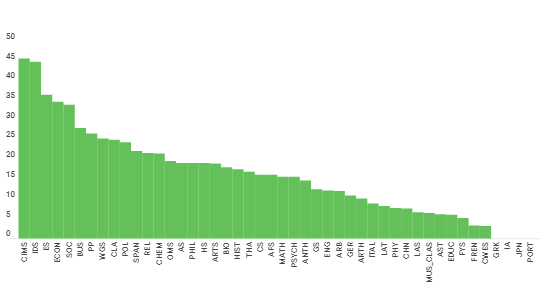

Percentage of courses above enrollment cap, Fall 2016-Spring 2020

“Course caps are set to provide students with the individual attention they deserve, but in Economics we simply cannot offer the courses students need to graduate without going over the caps,” Professor and Chair of Economics John Cadigan said of his department, where 35 percent of classes are overenrolled.

Professor of Cinema and Media Studies James Udden said that, in his program, which began offering a major in 2015, over-enrolling classes is a necessity due to lack of staff capacity.

“This is partially because I still teach so many of these courses myself, and I always go over the cap. But most of my colleagues who are all housed in other departments, but who offer courses vital to this major, generally do the same because I encourage that since we can only offer so many courses overall,” he said. “We have to do this because the demand far exceeds the staffing.”

He added that the situation has improved slightly with the addition of two new professors to the Interdisciplinary Studies program, which contributes courses to the Cinema and Media Studies major, but that more faculty members are needed to prevent such consistent high enrollments in the program’s classes and to help him sustain a program in which he is currently the only full-time faculty member.

“I still love my job despite the strains,” he noted.

Vice Provost and Dean of Arts and Humanities Jack Ryan said that faculty members have an expectation that “the playing field is even” with respect to course enrollments and could have a legitimate complaint about unequal workloads when, in some departments, faculty members’ total enrollment across two to three sections might still fall below the total number of students in a single section elsewhere.

He qualified that statement by noting that upper-level foreign language classes require individualized attention speaking and writing in the target language and that English courses—particularly those that meet the first-year writing requirement—have heavy workloads grading papers, which could justify small class sizes. (Ryan previously served as Chair of the English Department and continues to teach English courses each year.)

“We have to do this because the demand far exceeds the staffing.”

-James Udden, Cinema & Media Studies

Foreign language classes do have the smallest average enrollments, ranging from 4.7 in Greek to 14.4 in Spanish. English’s average class size is 14.8.

Associate Professor and Chair of Art and Art History Felicia Else defended low average enrollment in art studio classes, noting that safety concerns and space constraints require the course caps to be as low as eight, as they are for sculpture and ceramics classes.

Assistant Professor of Art Austin Stiegemeier added that teaching studio art classes requires unique preparation, individualized student attention, and cleaning and organizing spaces beyond what other faculty members do.

“The educational experience you can provide to each student may drastically be reduced by adding just a few more students to our studio arts courses,” he said. “You really have to keep this in mind when you consider comparing studio courses to other classes on campus that may be based on lecture or dissemination of information through oral and visual presentations and where students might be taking notes and participating in certain activities, but certainly aren’t building and creating physical objects during each class meeting.”

Larson, the political science chair, says that teaching both his department’s research methods course and capstone seminar require significant work from faculty members because each student is doing original research.

“Any kind of research effort like that is very intense and they are the hardest courses to teach,” Larson said. “We have had capstones with 22 people instead of 16 … it’s a pretty meaningful difference when there are five or six extra students in each capstone.”

The intense demands of supervising student research are not unique to political science. Monani noted that the Environmental Studies department had to open a second section of its capstone to accommodate student demand and that faculty members rotate who teaches it because of its demanding nature.

Average Class Size By Department, Fall 2016-Spring 2020 (Minimum 20 Courses)

As Cadigan, the former chair of the Faculty Finance Committee, observed, though, expanding one department would lead to cuts in another since the college resource base is, for now, relatively fixed.

Since 2009, the overall size of the college full-time faculty has remained stable, meaning that new tenure-track faculty lines in one department come from reallocating a vacated position in another. That means that some departments must make increasing use of visiting or part-time faculty members.

“There is some pressure on us to find good adjuncts,” Monani said of the Environmental Studies department, whose seven full-time faculty members, teaching five courses a year, would have to teach an average of 93 students in each class section to meet student demand without adjunct support.

But adjunct and visiting faculty do not advise students, which can put more pressure on a department’s full-time faculty members to serve as advisors.

In political science, which currently has two visiting faculty members and a first-year assistant professor filling three of the department’s 11 faculty positions and not serving as advisors, advising loads have increased significantly. Over the past ten years, the average number of advisees went from 28 to 40, Larson said.

Associate Professor of Political Science Roy Dawes said, “I have 40 advisees and unfortunately, cannot give them the time that advisors in other departments can give their advisees.”

Larson was more direct.

“We need more faculty members,” he said.

On the other hand, one department, Italian Studies, has more tenured faculty members than majors (two faculty members, one major).

Unequal advising responsibilities are not a new phenomenon. At a spring 2017 faculty meeting, Associate Professor of Health Sciences Josef Brandauer said that he had written 70 letters of recommendation that spring on behalf of his advisees. But with no expansion positions on the horizon, departments are likely going to have to continue with what they have.

Ultimately, classes of 35-40 students are not that large relative to other colleges, Professor of Philosophy Steve Gimbel said, noting that he taught at nine other institutions before coming to Gettysburg, sometimes having classes of more than 100 students. At a liberal arts college that prizes small class sizes, though, 35 “can feel large,” he said.

“A student can hide in the back row of a classroom with 35 students in a way that one cannot in a seminar of 8 to 12,” Gimbel added, noting that he works to make his larger classes feel smaller by, for example, meeting with students one-on-one to discuss their papers, which he allows them to rewrite an unlimited number of times.

“We need more faculty members.”

-Bruce Larson, Political Science

“On my end, it means more work. For that system to be effective, I have to turn papers around quickly and often read one student’s paper multiple times. I have to be very flexible with office hours that are not official office hours,” he said. “With a larger class, that can add up. But, it makes a difference in their academic experience and is worth it.”

Ryan said that the disparities in departmental enrollments merit a “thorough review” to make sure that resources are allocated appropriately. Overall, he thinks that 18 to 20 is probably the ideal course size, but getting there in every department—whether through adding more class sections taught by part-time faculty or by awarding new slots for full-time positions—will be tricky.

“There’s only one pile of money.”

Gettysburgian staffers Garrett Adams, Nicole DeJacimo, Phoebe Doscher, Lauren Hand, Carter Hanson, Gauri Mangala, and Katie Oglesby contributed to data collection for this story. Nicole DeJacimo contributed reporting.

This article originally appeared on pages 4-9 of the February 27, 2020 edition of The Gettysburgian’s magazine.