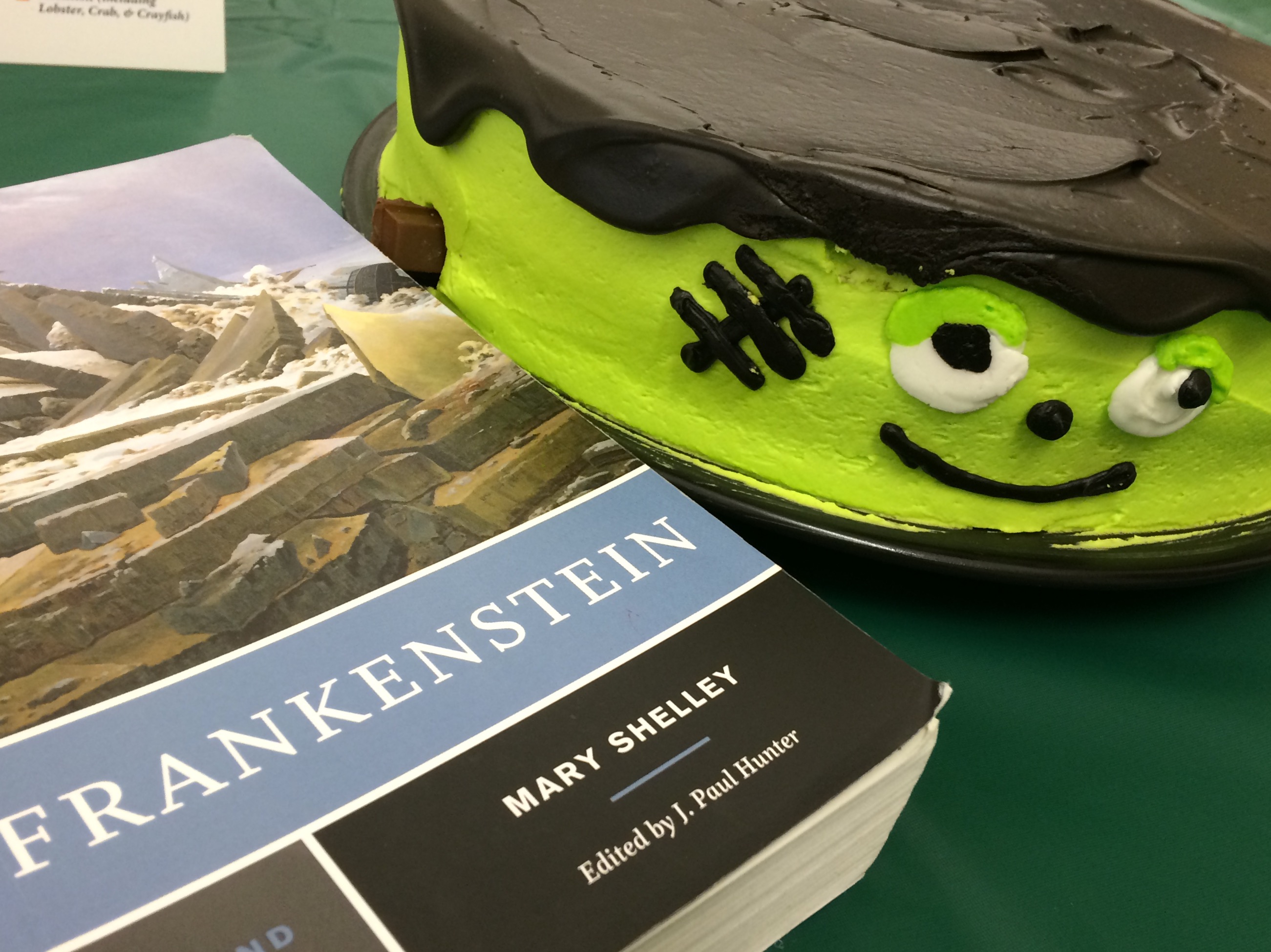

The Frankenreads event included fun Frankenstein-themed snacks and riveting conversations on the timeless classic (Photo Julia Chin/The Gettysburgian)

By Julia Chin, Staff Writer

The year is 1816. Dark clouds block out the summer sun, and night falls on the shore of Lake Geneva, Switzerland. Just over a year ago, Mount Tambora erupted in Indonesia, catalyzing a series of uncanny climate changes from its spewing of volcanic ash, which dropped the entire globe’s temperatures and stole the sun from the far corners of the Earth.

But in Europe, the cause of the unnatural phenomena remains unknown, causing speculations of supernatural events, mysterious factors, and a lingering sense of doom to rise from the waters of the lake like corpses from the grave. The assemblage of beings gathered inside Villa Diodati on the lakeside is a well-educated one, no doubt: candlelight illumines the anxious countenances of Lord Byron, John Polidori, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and his teenage wife, Mary.

Inspired by horror stories and the impending gloom, Byron suggests a writing contest, a study in ghost stories. The aforementioned quartet of company prep their ink and verses, not realizing that history is about to be made. Somewhere in the villa, nineteen-year-old Mary Shelley imagines the reanimation of a body. The birth of a corpse. She puts her quill to parchment and begins to write the lines of her legacy. Lightning strikes, and Victor Frankenstein recoils in horror as his creature is born.

October 31, 2018. It’s Halloween in the 21st century, a beautiful 64° autumnal day, and the trees on Gettysburg College’s campus are splashes of scarlet, crimson, and burnt orange. Yet, despite the inescapable presence of an advancing fall season, everything on the fourth floor of Breidenbaugh Hall is green. For today, green is the name of the game. Cucumbers, broccoli, and green peppers radiate from a circle of Green Goddess dressing. Sprite and limeade mix in a fizzy citrus punch that sits in a tall receptacle on a green tablecloth. Of course, it’s all for him, Frankenstein’s creature.

The infamous monster of the literary universe provides explanation for the other assorted hors d’oeuvres: “franks in a blanket,” colorful candy corn, and—my personal favorite—a shockingly chartreuse cake with frosted black stitches and Kit Kat bolts on either side of its neck. Its edible grin make me smile as I look upon the face of Mary Shelley’s creature, appetizer style.

Professor Goldberg has brought this event together to commemorate the Frankenreads initiative, a program thought of by the Keats-Shelley Association of America in an effort to promote global discussion of Shelley’s gothic novel. Today marks the 187th anniversary of the 1831 publication, the familiar edition; however, this is also the 200th anniversary publication of the first edition, the 1818 Frankenstein; Or, The Modern Prometheus.

“We’ve read the novel in English 345,” Professor Goldberg explains, “a course on the younger romantic writers—Mary Shelley, Percy Shelley, John Keats and Lord Byron, with Jane Austen also included (she’s twenty years older than most of the others, but her major novels came out at the same time that the others were active). It’s intriguing to look at the novel alongside work by her contemporaries, in part because of how Byron, Percy Shelley and Mary Shelley influenced one another and shared a common pool of preoccupations; in part because of unexpected analogies. An interest in the monstrous figures not just in Frankenstein, but also in Keats’s Lamia, for instance. The oddest analogy, one students haven’t yet talked about, is between Frankenstein and Austen’s Emma: each creates or recreates another who becomes a significant source of trouble.”

For the proposed four hours of discussion, Professor Goldberg has divided his class into three groups to lead guests in an engaged dialogue specifically regarding each of the three volumes of the novel. For a story that is quite concise—most editions don’t reach the couple hundred page mark—and centuries old, it still prompts people from all places to make their own inferences, interpretations, and inquiries of Frankenstein.

No theory is too far off from a well-wrought deeper meaning of the creature’s story, as parental ethics, the historical standard of science, double-consciousness, human compassion, and the ultimate question of what defines a monster are all brought into the conversation. Passages from Shelley’s work are read aloud to demonstrate both the artful technique and metaphorical evidence that make Victor and his creature come to life on the page.

On being asked why Mary Shelley’s magnum opus has endured for 200 years now, Professor Goldberg had this to say:

“I think the work has lasted—and still feels fresh—in part because it asks urgent questions about science, about our ability to manipulate our environment and about our ability to curb our creative abilities that play a crucial and inevitable role in modern culture. I cannot think of another text that so frighteningly embodies an abstraction in the way this novel does. But it has also lasted because of the dozens of theatrical and movie versions that have allowed for its constant reinterpretation since the first of the plays based on it came out in the early 1820’s. Shelley seems to have given subsequent writers a standing invitation to reimagine her story and to find new sources of terror in it. Anyone who has seen what Helena Bonham Carter does with the role of Elizabeth in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein from about twenty years ago will recognize a transformation to the novel’s plot that is fully in keeping with its premises, even as poignancy and horror surround the character in a way Shelley hadn’t envisioned.”

Through this precise explication, we can truly see that Frankenstein’s creation is a being that defies the laws of life itself: it never dies. Considering all the complexities and layers of depth that this novel offers, perhaps we should conclude the conversation on the perplexing question that even Professor Goldberg seems to be puzzled by: “Why is the creature green?” But, perhaps this is a mystery for next Halloween… We’ll all be dying to find out the answer till then.