Cassini Spacecraft Melts Orbiting Saturn

By Emma Gruner, Staff Writer

At 4:55 AM PDT on September 15, hundreds of scientists stood by as their precious, years-long project literally fell to pieces. Tragic as it may sound, the scientists were prepared – they knew this day was coming. Instead of weeping for what was lost, the researchers treasured the knowledge that had been gained, and, like true scientists, they moved on to the next big thing.

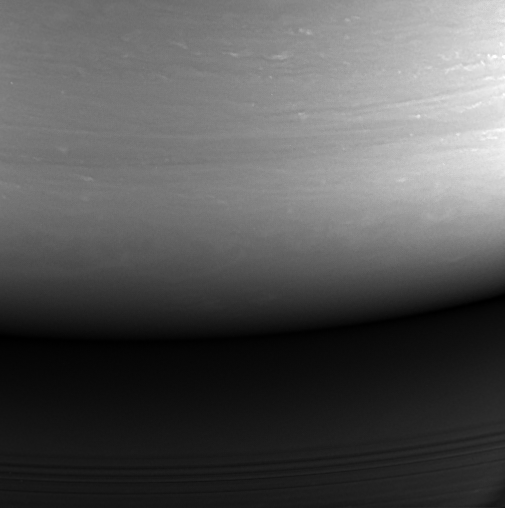

This “lost project” was none other than NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, which had been orbiting and collecting data on Saturn for the past thirteen years. Its mission had been long and fruitful, but its fuel was dwindling; in order to avoid contaminating the planet’s moons, the scientists manning Cassini sent the spacecraft straight into Saturn’s atmosphere. Traveling at about 113,000 kilometers per hour at about 10 degrees north of the planet equator, Cassini met its end, melting into the elemental abyss.

The Cassini project was remarkable not only for its duration, but also for the breadth of the scientific community that it spanned. While the mission control for Cassini was located at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, the research team included an impressive roster of both American and European specialists. Johns Hopkins University, University of Colorado Boulder, Imperial College London, Sapienza University of Rome, and many other institutions were represented on the Cassini team. With so many minds working on the project, it’s only natural that it would yield a staggering wealth of data – now that the mission has completed, it’s time to get down to the “dirty work” of analyzing it.

The research team went into the project with a few clear objectives in mind – one was to determine the age of Saturn’s rings, which had been estimated at anywhere between 100 million to one billion years old. During its last 22 orbits, Cassini had been collecting regular data on the rings’ chemical composition and gravitational attraction, both of which play into age calculations. While the team is not yet prepared to give a definitive answer on this matter, they will say that, unlike some had previously thought, the rings probably did not form along with the rest of the planet.

Another primary area of study was Saturn’s magnetic properties, which yielded some interesting results. They found that Saturn’s axis of rotation and were almost perfectly aligned; according to previous models, there needed to be some offset in order to maintain a magnetic field. As Michele Dougherty of Imperial College London says, this finding ““suggests that we don’t really understand Saturn’s internal structure and how the planetary dynamo is generated yet.” The team also had hoped to determine the exact length of Saturn’s day by measuring radio bursts – a method that had proved successful when studying Jupiter. Yet they found these bursts to be too irregular, meaning their best guess at the planet’s day length is anywhere between 10.6 and 10.8 hours.

The most groundbreaking outcome of Cassini by far, though, is the data collected on two of its 62 moons – Titus and Enceladus. Thanks to the spacecraft’s efforts, these two moons have become prime candidates in the search for life. On Enceladus, more than 100 plumes of hydrogen-rich liquid water were found erupting from surface cracks. This teases the presence of hydrothermal vents below the moon’s surface, similar to those present on Earth. Titus, on the other hand, boasts vast landscapes of rivers and lakes filled with liquid methane – the only recorded instance of surface liquid found on any non-Earth celestial body.

The Cassini team still has one more year of funding left, during which they plan to analyze the monumental collection of data. Early indications show that the findings from this mission could alter our entire understanding of extraterrestrial science. As Dennis Matson of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory says, “Before we got to Saturn, I didn’t expect it—I thought it’d be like Galileo at Jupiter. I didn’t expect it to be a paradigm reset of everything.”

While there are currently no U.S. plans in place to return to Saturn, some proposals have already been submitted to NASA for review. There is, however, a Jupiter-bound Europa Clipper mission launching soon, for which orbital innovations from Cassini will be used to help avoid harmful radiation. There are also planned missions to Jupiter’s moons, to Uranus and Neptune, and back to Saturn’s moons to search for life – missions which many Cassini personnel will be taking part in. While it’s absence is sorely missed, Cassini the spacecraft will certainly not have died in vain!