Why the Republicans should be taking the L…back

By Alex Romano, Opinions Editor

Liberal. The mere mention of the word conjures up images of frantic college-age yippies waving boards and signs in protest of the Trump administration on the White House lawn; of massive welfare programs keeping the working-class American family afloat in times of economic peril; of gussied-up bureaucrats laying on heaps of red tape on Cabinet departments and executive-level agencies in Washington; of well-meaning and effective laws protecting the environment from depletion and degeneration; of Clintons, Gores, Kennedys, Carters, Roosevelts, and Johnsons.

As the previous sentence intends to illustrate, the word “liberal”, like any other word, finds itself in association with other terms and imagery both good and bad.

However, there was a time when liberalism did not mean what it does today, when all of the aforesaid items had no attachment to the liberal school of thought.

“Liberal” nowadays means “progressive”, and is universally accepted as a descriptor of the Democratic Party, the Left that stands primarily for tolerance, social justice, institutional reform, fair economics, and national progress at all levels. For decades, this has been the case. While everybody may be able and willing to identify these concepts with liberalism, it may not be the best case to do so.

Philosophers and historians generally agree with the claim that liberalism began with John Locke, the author of such renowned works as “An Essay Concerning Human Understanding”. Through his writings, Locke preached that man was entitled to natural rights and liberties, including the practice of religion free from persecution; the acquirement and ownership of private property; and a governmental separation of powers to preserve democracy and prevent the growth of absolutism.

Locke also endorsed the idea of a social contract, an arrangement in which the citizenry forfeits some of its individual rights in exchange for governance and the protection of its remaining civil liberties. From Locke’s works came the term “classical liberalism”, an important ideology to remember, and one to which countless people subscribe without knowing it.

To further straighten out the alignment of classical liberalism with modern-day Republicanism, the spotlight must move to Adam Smith, the great Scottish philosopher and creator of such famous concepts as the “invisible hand” and the division of labor.

In the course of his writings, notably “The Wealth of Nations”, Smith applied the theory of classical liberalism to economic theory, using the concept of pursuing self-interest inevitably generating improved welfare and added benefits to be shared in the society as a whole; man’s right to full control over private enterprise; an emphasis on wealth; and the blockage of governmental interference in the free market system to create the ideology that is essentially today’s version of capitalism.

After Smith’s time, the laissez-faire system became a serious, highly consequential and influential element of the global scene.

Even left-leaning thinkers sided with the thought behind this massive free market. John Stuart Mill, the old champion of civil liberties and forward-thinking member of the Liberal Party in Great Britain, admitted in his writing that while the free market had its problems, it was the best deal that the world could ever hope to get.

To compensate for its inadequacies, Mill advocated for a minimum standard of living to be provided to every one person and family in nations under capitalist control.

He also argued for women’s suffrage, enhanced education opportunities, and a number of other initiatives in the name of social progress. Of course, that he refused to completely comply with only one side may to some be admirable, as it makes him more of a middle-course man and a compromiser, but the fact remains the same: with Mill, we begin to see where the lines between the liberalism of old and the liberalism of new blur together. A fiscal conservative, but a social progressive. Now how could that be?

Fast-forward to the twentieth century, with the election of Republican Herbert Hoover as president of the United States in 1928. Hoover was an accomplished man, an honest secretary of commerce, an unbelievably skilled, smart, and competent engineer, and the country’s leading figure in the Efficiency Movement. He was also one of the worst leaders that our country has ever had to endure, allowing the country to slip into economic depression and tear itself apart.

But, when he became the thirty-first president, Hoover wanted to coin the term “liberal Republican” to describe his party, a name that would have united the traditional concept of classical liberalism with the current American political philosophy of Republicanism. This would have made it so that Republicans would have been more liberal than the Democrats of today, albeit in a decidedly different sense.

Instead, Franklin D. Roosevelt became the president to commandeer the word liberal, adding a neoclassical spin to the term. And since his New Deal policies represented a tremendous departure from the popular economic theory of the day, those who objected to the novelty of his approach became conservatives.

Since they were chiefly Republicans, they became known as conservative Republicans, and Hoover never got his wish.

So conservatism became a different economic philosophy from liberalism entirely, causing the definition of the word liberal to change considerably from its original meaning. But what seems to be forgotten in today’s world is that liberal has not always been the word to describe social change or industrial regulation.

Rather, the word “progressive” was the label initially coined for the advancement of these purposes.

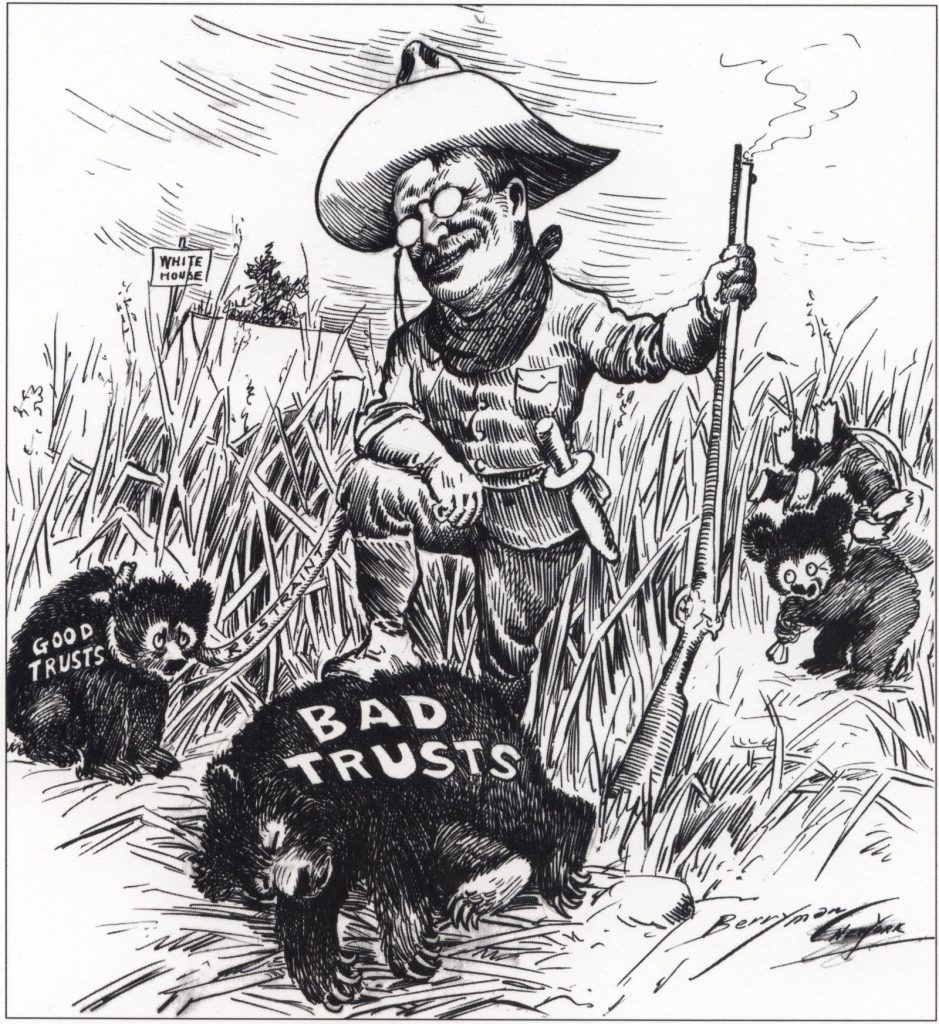

President William McKinley, whose presidency has undergone a significant positive reassessment recently, suffered assassination at the hands of an anarchist, and was succeeded by Theodore Roosevelt, who looked upon McKinley’s ignoring of the follies and buses of big business as the chief domestic failure of his predecessor’s administration.

Along with trust-busting, TR also focused on environmental protection and food and drug safety as major policies for his administration. Woodrow Wilson continued the progressive trend, which was revitalized and re-strengthened by FDR, and virtually every Democrat after. (I myself can think of only one Republican since TR whose administration boasts an honest-to-God progressive record, but for the sake of avoiding controversy, I will refrain from mentioning his name, which on its own is enough to inflame people’s feelings.)

Fast-forward again, to the 1980s, after Lyndon B. Johnson effectively tied social issues into economic policy with the Great Society.

In response to LBJ’s newest deal, and the countercultural movement of the 1960s and decisive national unrest of the 1970s, President Ronald Reagan saw the time right to roll back some of the progressive legislation passed through the Kennedy-Johnson years and emphasize evangelical Christianity as a significant component of the Republican Party. The result of this mission was the founding of the modern neoconservative sect, a group who has been the subject of my ire and distaste for as long as I can remember, a militant faction whose values and principles have formed the school of thought known as social conservatism. And that is where the Republicans got slapped with the conservative label for good.

So, if the Republican Party is conservative in the social sense now, then what’s wrong with using the word liberal, already by the age of Reagan a term associated with the Democratic Party?

There are two answers for that. The first is that since liberal was originally intended for use only in relation to economics, and progressive only for the cause of social change, it makes no sense to call Democrats’ social policies liberal. It would make more sense to call them progressive, as well as the Democratic agenda in terms of the economy.

The second reason is that the word “conservative” in modern times is synonymous with the words hateful, repressive, square, and avaricious, due to the social aspect of conservatism.

While this is the GOP’s own doing, and social conservatism is not my personal cup of tea, it really makes a negative first impression on some members of opposing parties (especially on a liberal arts campus) when one introduces oneself as a Republican, as the assumption is that if you are a Republican you are also conservative. And from that assumption, more are to come.

So that is my case. Republicans should have the L-word back. To simplify things, this way we would have Democrats as fiscal progressives and/or social progressives, and Republicans as classical liberals and/or social conservatives.

Of course, you will have classical liberals and social progressives, and maybe even fiscal progressives and social conservatives (in circumstances that I cannot currently imagine), for not everybody is tilted entirely one way or the other. But, anyway, man, would this change of labels make things easier.

July 22, 2018

The progressive Republican since TR was Nixon right?