International Affairs Program Hosts Panel on ‘America First’ Trade Policy

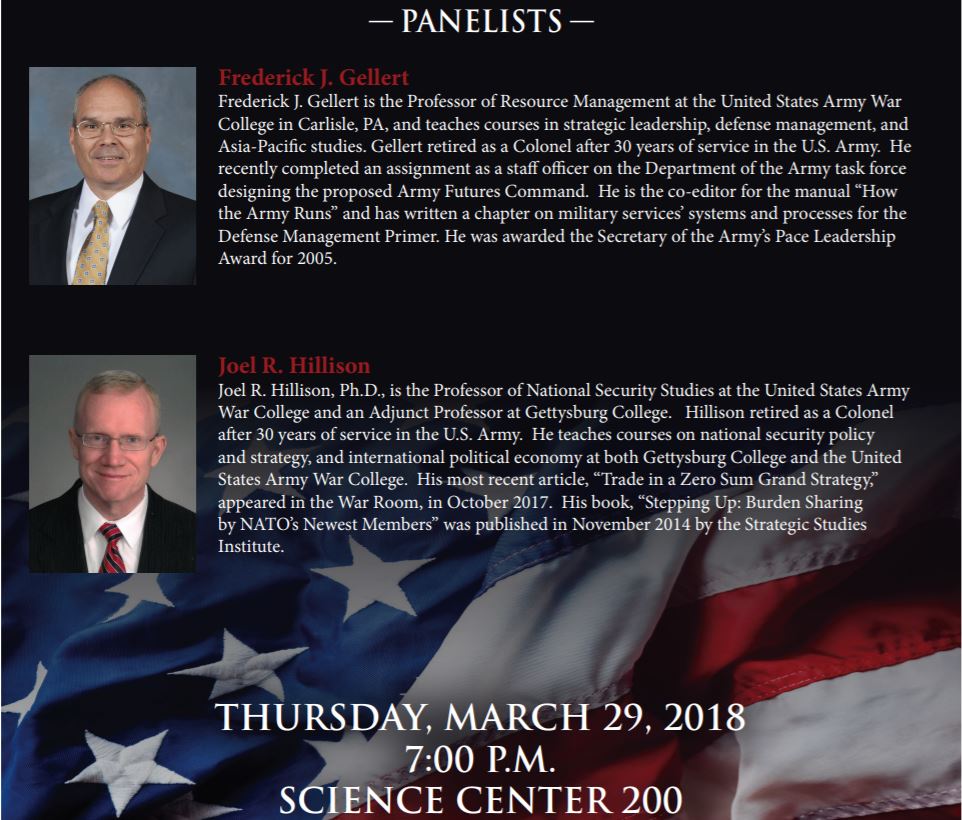

Event poster for panel led by Professors Frederick Gellert and Joel Hillson (Photo courtesy of Gettysburg College International Affairs Program)

By Sarah Hinck, Staff Writer

Last Thursday, the International Affairs Program hosted a panel on U.S. Trade Policy. The panel was led by Professor Frederick Geller and Professor Joel Hillison from the U.S. Army War College; the latter is also an Adjunct Assistant Professor in the Political Science Department here at Gettysburg College.

The first portion of the panel was dedicated to discussing the history of trade in the U.S. As a colony, the U.S. traded primarily with Great Britain, and in the era of colonialism, the international trade system was dominated by mercantilism. Colonial powers such as Great Britain would seek to export more than they imported in order to produce greater revenue. They would trade solely with their own colonies, as trading with other colonies would result in a zero sum game. After gaining independence, the U.S. sought protection for its industries. Individuals such as Alexander Hamilton supported engaging in protectionism in order to allow for the young nation to expand and gain strength until they could vie with the competitive markets of other countries.

Industrialization and globalization during the early twentieth century welcomed free trade, though both World War I and World War II disrupted the markets. Geller noted, “A lot of times in our history, trade was not just an economic issue. It was a security issue,” when discussing how tariffs—once a source of revenue—were lowered by President Roosevelt right before the U.S. entered WWII. He went on to say that conflict and or war when there’s infringement on trade.

The panel highlighted some of the numerous actors that are involved in U.S. trade policy: the State Department, Department of Treasury, Congress, the Executive Branch, and the Department of Commerce. Each actor plays a different role, whether it be implementing sanctions or conducting arms trade. Hillison explained that Congress frequently delegates matters regarding trade policies to the executive branch, which can accelerate the process of approving trade deals, as Congress simply takes an up-or-down vote on whatever the executive branch negotiates rather than having the opportunity to offer amendments.

In regards to whether the U.S. is in a trade war, the professors noted that the U.S. has placed 60 billion dollars in tariffs on China due to theft of intellectual property, yet the Trans-Pacific Partnership, from which the Trump administration withdrew, had protected intellectual property. In regards to abandoning TPP, the professors asserted that there were those who worried that some of the labor markets in the U.S. were losing out on profits.

The Q&A portion of the panel was centered heavily on China and how its president, Xi Jinping, is seeking to “change made here to designed here” in order to foster more innovation within the nation. The issue of intellectual property has been changing trade policies and manufacturing rights. Hillison quoted Xi, who, to some extent, has replaced the United States as the world’s leading advocate for free trade when he said, “We have to stand up for free trade.”

Gillert echoed that sentiment near the end of the panel in response to a question about whether institutions will help work out unresolved tensions on trade.

“We have no choice,” he said. “We have to trade. We have to try to help our economies … Fundamentally, you have to have a rules-based order or it’s chaos trying to deal with this stuff.”