Prof. Wendy Piniak helps foster passion for science

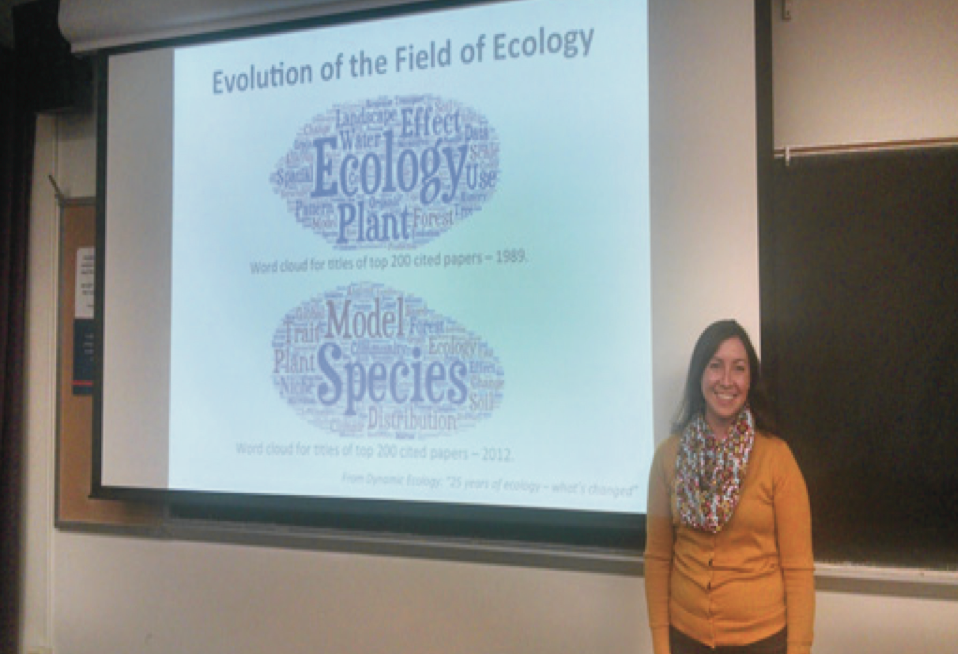

Professor Wendy Piniak presents a Powerpoint of the “Evolution of the Field of Ecology.”

(Photo credit: Stephen Lin)

By Stephen Lin, Staff Writer

It is 8:30 in the morning and Wendy Piniak, the new ecology professor at Gettysburg College has been tasked with educating a combination of tired and possibly hung over students. The classroom falls silent as students attempt to jumpstart their brains with the task at hand. I shuffle through my notes, knowing that the answer is not there. Just as the silence starts to grow uncomfortable, someone in the back row mutters an answer and we let out a collective sigh of relief.

“Can you speak up, so the whole class can hear?” asked Wendy, who prefers a first name basis rather than the formalities of the professor title.

“It’s gotten more specific,” said the student sheepishly. Indeed, the field of ecology has changed drastically even since Wendy graduated from Gettysburg College in 2003. She has since participated in a variety of graduate research on sound and sea turtles, ranging from the policy discipline to the hard sciences, all culminating in a Ph.D. at Duke University in 2012. With all of this interdisciplinary experience, Wendy has now returned to Gettysburg College to help foster a passion for science so that students can also help advance the ever-growing field of ecology.

Ecology from 1993-2013: The Doc Years

ES 211: Principles of Ecology has typically generated a lot of nervous energy amongst Environmental Studies majors. It is the class that tends to weed out students on the fence about the major because it has a reputation for being very challenging, a real GPA-dropper, if you will. But this year some students believe it will be different, “There’s no way she’s going to be as tough as Doc was,” whispered one student before class started.

It is hard to ignore the big hole that John Commito, or Doc as most students call him, has left since taking sabbatical last year. Having never taken his class before, he still knew me by name and often complimented me after jazz concerts. All I knew about him was that his labs were next to impossible, but well worth it in the long run. Doc’s departure and Wendy’s arrival left me with a mixed feeling of disappointment for being robbed of his wisdom, relief about having a less intense ecology experience, and an overwhelming amount of uncertainty. Is this class going to push me over the edge and make me want to change my major? Will I have the skills necessary to pursue science without Doc’s revered instruction?

“She’s like a mini-Doc,” says Brian Lonabocker, PLA of my ecology lab section. “She was hand-picked by Doc,” he assures me. Both graduated from Duke with research focused on Marine ecology, and Wendy herself was a student of Doc’s. Brian describes Doc as “old school, strictly chalkboards.” Unlike Doc, Wendy’s teaching style integrates a lot of new technology such as PowerPoint presentations and video abstracts.

Now sitting in her turtle themed office, where students can more than likely find her for extra help, Wendy smiles, thinking back to her time as a student at Gettysburg. “I think we were still using AOL chatting—there was no texting,” says Wendy. “Part of one of the goals of a teacher is figuring out the most efficient ways of teaching. I know you guys use Google docs and there’s no right or wrong way. Doc’s way worked.”

Wendy has balanced her style of teaching with Doc’s more traditional approaches by checking with the PLAs, who had ecology with Doc to see what was most effective. “Sometimes it doesn’t work out perfectly, but what’s important is that you guys work it out together.”

In many ways the collaborative nature of research reflects how the field of ecology has grown since her time at Gettysburg. “It’s so much bigger,” says Wendy, answering the question she posed in her earlier PowerPoint. “Collaborative work has become way more common than it was 30 years ago because now it is hard to be an expert in all of those fields.”

At the surface, group work means a lot less work for myself, but it involves a lot of accountability from your peers. I have been in the unfortunate circumstance of having less than responsible lab partners and felt cheated of a decent grade, but group work is one of the key principles of the Environmental Studies major and the field of ecology. It is a principle that Doc had always emphasized and that Wendy continues to reinforce despite their differences in teaching style.

From GIS to statistical models to policy making, ecology is definitely a buzzword with all of the interdisciplinary fields it involves. With this in mind, Wendy remarks that, “Nobody can be an expert in everything and we really learn more by bringing all of those things together.”

That said; collaboration is still no easy task. Since taking ecology, I have had to learn how to properly manage my time so that I can work collaboratively with my peers. With time management, each member

of a group can contribute their knowledge of various disciplines in which they specialize to the overall research. The field of ecology and environmental studies in general is unique in that there are many lenses through which we can understand it. Collaborative writing is important in that it forces us to bring these lenses together for a better perspective.

During Wendy’s fellowship at the National Marine Fishery Services, the people she worked with came from completely different backgrounds and had very different perspectives or as Wendy calls it, “languages.”

“We’re training you all to speak both of those languages,” says Wendy. “If you want to do applied science, you need to understand how it works in the policy world. We need a whole new group of people who are truly interdisciplinary and understand both sides. It is the goal of the department to teach you guys to speak both languages.”

Wendy is at the forefront of this new world of people. She has an M.E.M in Coastal Environmental Management and a PhD. in Marine Science & Conservation. “I think what often happens is that scientists do the research and policy makers don’t use it and when I was doing my research I was like, ‘I don’t get it,’” she laughs. However, Wendy feels optimistic in that this gap of understanding is closing and that “there is a whole new generation of people like [herself] looking to bridge that gap.”

Bridging the gap between policy making and science is no easy task, just like collaborating on group papers. We can argue about the nuances of the best way to approach this timeless puzzle—the Doc-way or the Wendy-way, chalk or PowerPoint, but it all boils down to one thing.

I asked Wendy about her long-term goals as an ecologist and she told me, “I hope I end up at some sort liberal arts school like Gettysburg because I have a very interdisciplinary background, which is a fit for an Environmental Studies department.”

It is the interdisciplinary nature of the Environmental Studies department that allows us to grasp the various concepts surrounding environmental issues so that we can, as Wendy put it, “marry policy with science.” This is put into practice through the collaborative research that Environmental Studies majors participate in. Professors such as Wendy and Doc, regardless of method, have fostered this principle both their work and teaching.